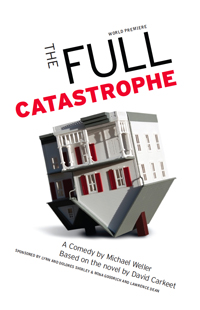

The Full Catastrophe

A Comedy by Michael Weller

Based on the novel by David Carkeet

Directed by Ed Herendeen

WORLD PREMIERE

Sponsored by Lynn and Dolores Shirley & Mina Goodrich and Lawrence Dean

Dr. Jeremy Cook has a problem. While he is a linguist (of moderate renown), he is also unemployed, broke, and haunted by the words of an old friend who says that basically, ‘his timing sucks majorly.’ In desperation, Cook accepts an offer from the enigmatic Roy Pillow to serve as part of a research experiment, living with a married couple as their relationship counselor. However, Cook’s lack of: a) experience b) understanding of love c) history of successful relationships d) common sense and e) instinct – guides this couple from a dysfunctional marriage toward the hilarious “full catastrophe.”

Dr. Jeremy Cook has a problem. While he is a linguist (of moderate renown), he is also unemployed, broke, and haunted by the words of an old friend who says that basically, ‘his timing sucks majorly.’ In desperation, Cook accepts an offer from the enigmatic Roy Pillow to serve as part of a research experiment, living with a married couple as their relationship counselor. However, Cook’s lack of: a) experience b) understanding of love c) history of successful relationships d) common sense and e) instinct – guides this couple from a dysfunctional marriage toward the hilarious “full catastrophe.”

MICHAEL WELLER

Michael Weller is best known for his plays Moonchildren, Loose Ends, Spoils of War and his trilogy including What the Night Is For, Fifty Words (MCC), Side Effects (MCC). He wrote the Book for the musical Doctor Zhivago, from the novel by Boris Pasternak, which opens on Broadway at the end of March.

His films include Hair, Ragtime and Lost Angels and a teleplay of his Broad-way drama Spoils of War, starring Kate Nelligan. He was a writer-producer on the critically acclaimed series “Once & Again.”

Awards: Academy Award nomination; N.A.A.C. P. Outstanding Contribution Award; Critics Outer Circle Award; a Rockefeller Foundation Grant; a Kennedy Center Fund for New American Plays Award, and a Helen Merrill Award for playwriting.

Marinoff Theater, Center for Contemporary Arts/II, 62 West Campus Drive

Run time: 90 minutes

CAST

Jeremy Cook…Tom Coiner*

Roy Pillow…Lee Sellars*

Beth/Paula…Helen Anker*

Dan Wilson…Cary Donaldson*

Robbie Wilson…Sam Shunney

Everyone Else…T. Ryder Smith*

Understudy, Robbie…Adam Venham-Carter

*Actors’ Equity Association

CREATIVE TEAM

Set Designer Peter Ksander

Costume Designer Therese Bruck

Lighting Designer D.M. Wood

Sound Designer Elisheba Ittoop

Technical Director Josh Frachiseur

Production Stage Manager Deb Acquavella

Interview with Michael Weller

Researched, interviewed and edited by Sharon J. Anderson, CATF Trustee/Professional Story Listener and Creative Director

CATF: “The Full Catastrophe” is the middle book in The Jeremy Cook Novels by David Carkeet. Why write a play adapted from this book?

MW: The book was brought to me as a film project by the producer Merle Kailas, who had seen a play of mine and thought I was very good writing about marriage. The novel had had a big life with the Hollywood studios when it was first published, but no one had been able to figure out how to do it as a movie. I read the book and realized it would make a terrific play.

CATF: Why do you write marriage really well?

MW: Good question. I’m married, and I notice it.

CATF: But why write about it?

MW: Drama is about conflict and the solution to the conflict and renewed conflict. Isn’t that another way of describing marriage? It seems like a fairly natural thing to put on stage. One of the basic rules of drama is pick something everyone knows. Marriage is something that everyone knows.

CATF: Jeremy Cook, the main character in “The Full Catastrophe,” is a linguist. So marriage is about semantics?

MW: That’s the joke, and it’s a wonderful one. The lovely conceit of the book is that a crackpot, mysterious researcher called Roy Pillow thinks he’s solved the problem by what turns out to be a linguistic mistake of his own: thinking that communication means better grammar. It’s of course about something very different, but the misunderstanding is, for me, one of those profoundly brilliant comic conceits that yields all sorts of dramatic possibilities.

CATF: Roy Pillow, the “crackpot, mysterious researcher” said in this play: “There is a horror at the heart of every marriage and it’s the same horror.” Is there a horror at the heart of every marriage?

MW: So he says.

CATF: Do you think there is?

MW: No, not really. I think that he thinks so and his marriage record certainly bears that out. It’s not a horror, but what’s puzzling about marriage is that we’re so drawn to it and it’s such a source of discomfort when it’s bad and such a source of support and joy when it’s good. And we just can’t figure that out, why it can’t be simpler, like an ATM machine. Marriage is a total swirl – call it a “horror” if you want. For me, it’s a comedy if you simply exaggerate what is really the case.

CATF: I asked the playwright Bruce Graham, who had a comedy at CATF last year, about Coleridge’s perspective that comedy was “more useable and more relevant to the human condition than tragedy.” What do you think about that?

MW: It depends on where you’re sitting and how you’re doing in life. People whose wives are taken away by invading armies or who die of horrible diseases or work long, long hours every day would feel that tragedy is a comfortable portrait of their destiny. But a comedic outcome feels far more real in America, where we tend to go to therapists when we’re on the verge of some personal catastrophe and they help us talk ourselves out of it.

CATF: One of the lines in this play is “Recognize love in time or you’ll lose it.” What’s the secret to recognizing love in time?

MW: You have to have the courage to risk love at all times. If you hedge your bets because you think this isn’t right or that isn’t right about another person, then you really will misunderstand which part of that complicated feeling toward them is the important one.

CATF: So love is worth it?

MW: I think it is. I just don’t understand an approach to life that doesn’t involve trying to communicate completely with another person – or with a lot of people. Otherwise, why would I be a playwright? I’m there trying to reach a lot of people because I think feelings inside me that ordinary, day-to-day interchange don’t allow to come out easily can be beautifully achieved on stage. And they can be beautifully achieved in an intimate relationship if it’s a good one.

CATF: You have said that when you work on a play you’re on a journey of some kind. “It’s where I am in the bigger journey of a play and what I’m trying to work out in it that matters to me.” What kind of journey are you on in “The Full Catastrophe?”

MW: “The Full Catastrophe” is a commission, so my quote doesn’t entirely apply here. Generally, when I’m working on a play of my own, I don’t know why the journey calls me to take it. Once the journey starts, I’m following a series of unstated questions inside myself. Not questions like “What’s green and has three eyes?” but rather, “What can happen in a scene by the time it’s over that I will think is true and will persuade and satisfy me?” Usually it involves something deep inside me that I can’t talk about any other way.

CATF: An October 2008 New York Times review of your play “Fifty Words” says that your plays are “propelled by a longing to be alone and a longing to never ever be alone.” With that in mind, how do you respond to this line from David Hare’s 1985 movie, Wetherby: “If you’re frightened by loneliness, never get married.”

MW: That’s very David. The writer’s dilemma is that they want by turns to be completely known and they want to remain completely concealed. There’s a push-pull at the center of the act of writing that’s inherent. I think it’s cavalier of David to put it that way but I know how he does his business in a play and that’s a likely statement from him. I just don’t agree with him and on some very fundamental level. He and I are totally opposite human beings in the way we experience the world.

CATF: Do you ever wake up and say, “Who the hell is this person next to me?”

MW: Oh no. I understand and know my wife very well. I do sometimes ask, “Why the hell is she like that? Why can’t she see that? This is ridiculous what she’s doing.” But I know exactly why she’s doing it. At least I’ve explained it to myself.

I spend a lot of my time observing people. This is the cruel thing about being a writer. You do watch people carefully and you sometimes come to understand them very well. But I never ask, “Who is this?” It would be very, very difficult for my wife to completely surprise me. She often surprises me in small ways, but if she did something entirely out of character, I would really be thrown by it.

CATF: In “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” the character George Washington describes his relationship to Martha as “Dashed hopes and good intentions: Good, better, best, bested.” What do you think of that?

MW: I know Edward Albee a little, and I understand how he arrives at that idea. That’s just not my experience. As an outsider to marriage – Albee saw his own parents’ marriage through the eyes of an adopted child, and that’s a very specific perspective to bring into the world . . . my experience of life is not that.

When you become close to somebody and you truly love them, there’s a part of you that’s sometimes startled by the fact that they don’t understand how both godly and how flawed you are. They don’t always bring the exactly right amount of respect and comfort you expect. That’s a very useful thing because it helps you see that sometimes you’re an arrogant asshole and you really need to be humbled a little bit and be glad that somebody’s so willing to remain with you.

CATF: This play makes several references to listening – “We should all listen more carefully.” How has listening helped your marriage and your craft?

MW: Listening helps everything. People are amazed when you listen. When you hear beyond what they are trying to say to what they are trying to say underneath, it’s a big gift for them. But it’s also a big gift for you. From a writer’s point of view, we’re dealing mainly with the visible universe. We’re reporting what can be observed. But we’re also always trying to suggest the shimmer behind it. If you listen carefully for the little doors that open in a conversation, doors to what you know someone is not telling you, you get better at creating a world with surfaces that suggests a lot of unstated intention beneath and behind the words. Audiences like that.

CATF: You have said that the mirror neurons in the brain are more powerfully activated by a play than by other media.

MW: If you see a photograph of somebody being killed by another person, it’s shocking. But if you actually see the person killed, it’s devastating. A live experience is inescapable. In film you’re so used to seeing those images you tend to dismiss it as just another image. But when a person’s in front of you impersonating the emotion and the action – even though you know they’re faking it – you get completely lost in their act of doing it because they are physically in front of you, embodying it.

Theater is a tribal act. We’re doing something very primitive during a live performance: We’re tracking game. We watch actors on stage, and we become hunters watching characters who don’t know we can see them. Of course, we know they know, but at the moment we are completely engaged with them, we are stalking prey, watching every move to see which way they’re going to go. Watching live action is very, very primitive.

CATF: What’s distinctive about producing a play with the Contemporary American Theater Festival?

MW: It’s a theater with a real artistic director. Ed reads every play. He doesn’t give it to a committee. His taste is so wonderfully eclectic, and he loves theaters and plays. It’s the way the great artistic directors that I love have operated – Joe Papp, etc. They had a theater, they knew what they loved and didn’t apologize for it. They put it out there and the only common thread was that there was a strong personality making all the choices. I love being a part of the family of choices he makes.

CATF: Barbara Hammond ended a piece she wrote entitled, “How to Stay a New York Playwright” with this: “Now close your eyes again, envision a stage, and watch someone walk on from stage left. Get that pencil and write down what she says.” My last question to you: Close your eyes, someone is walking on from stage left. What is that person saying?

MW: I have no idea. Until there is a context, I don’t know where to begin. For me, until there’s a situation, there’s no drama. I think the world is a set of conditions into which you put a disruption and then . . . you watch.