Researched, interviewed and edited by Sharon J. Anderson, CATF Trustee/Professional Story Listener and Creative Director www.sharonjanderson.com

CATF: Why did you write a play about a marriage set in a Red State?

EL: I wanted to write about a marriage that not many other people would think of as successful and put it to the test. I wanted to write a play where people would want to root for the marriage and would want to root for the husband and wife because I believe in their tenets. Even with this mistake between them I still thought that this marriage deserved a shot.

In your play, the wife, Laurel, says, “I will have two rules. Love each other and tell the truth.” Are those your tenets?

Those tenets, those rules emerged within my family. As you grow up, you learn how to be friends with your siblings and your parents, but you also realize that you are always going to fight with each other. You don’t fight with anybody like the people you love the most. Whenever we had an argument or disagreement, we eventually realized that everything boiled down to loving each other and telling the truth. My family learned those rules together and knew that they would always keep us together.

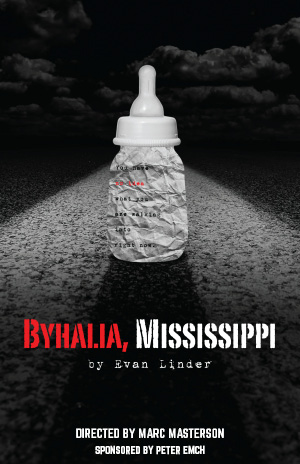

The themes of marriage and family notwithstanding, Byhalia, Mississippi was, in 1974, the location of one of the longest civil rights boycotts in American history.

The boycott was the result of the shooting of a black youth – Butler Young, Jr, who is mentioned in the play – by a white policeman. Young was in the back of a police car and according to police, Young escaped from the car, and while running away, ran into a fence and broke his neck. The coroner discovered that he did not have a broken neck, but a bullet wound. That sparked protests led by a man named Skip Robinson – also mentioned in the play – the founder of the United League of Marshall County. This boycott went on for almost a year and a half and closed many businesses in Byhalia.

It was tough to find that history, but I researched everything I could about Skip Robinson and discovered he had a niece who was an actress living in Chicago. She was the understudy for Ayesha in our Chicago production world premiere.

A review of Byhalia, Mississippi said, “No honest story about the South could be told without the acknowledgment of its wrongs at the forefront.”

The only way, to quote Laurel in the play, is that people “are forced to watch it happen.” That’s why telling the truth becomes such a cornerstone of her life because she believes that if you don’t look at mistakes you’ve made, you’ll never be able to look past them.

You quoted Faulkner in an interview: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” About Jim’s perceived racism, his best friend, Karl, says in the play, “Something in you thinks I’m less than you. You got that shit inside you. Always have.” Do we all have that shit inside us?

I think we do. We are products of our environment. We have things in us that we are always trying to overcome so we can be better people. Everybody in this play goes on a journey of trying to be better, even Laurel’s mother, Celeste. At the end of the play, we, for the first time, witness some calm and sweetness between Celeste and Laurel. I see someone who is trying really, really hard. Unfortunately, Celeste has much more of that “shit” in her than any of the other characters because she has solidified herself in that environment. She wants to help her daughter get through this and doesn’t know if she can because her religion has taught her that Laurel is a liar, a cheater, and a whore.

Despite that, there’s a lot of humor between Laurel and Celeste . . .

I didn’t set out to add humor because the situation of the play warrants it or the audience is going to need some breaths or moments of relief. I wrote it because I know these women, and they’re funny and they know they are funny. Even though they’re fighting, there’s part of both of them that loves that. I just wrote these characters and it’s inevitable that humor would come out of their mouths.

An article in the March 27, New Yorker, reveals how Pulitzer-prize winning playwright Lynn Nottage spent two and a half years in Reading, Pennsylvania to better understand how the livelihoods of the characters in her play, Sweat are threatened by the evaporation of manufacturing jobs in America. Nottage says, “One of the mantras I heard the steelworkers repeat over and over again was, ‘We invested so many years in this factory, and they don’t see us. We’re invisible.’ I think it profoundly hurt their feelings.” Did you write this play to make Red State citizens more visible because they are among those President Trump calls the “forgotten people”?

Yes, that’s why I loved writing and working on this play because I wanted them to be seen. At first, I was writing this for a Chicago audience – that’s who I usually write my plays for because that’s where all my plays are usually produced. But about halfway through, I decided to try and see the show through the eyes of a Memphis audience. I started smiling and thought, “Man, how much they would like to see people they all know up on stage.” So I began to look at my play through the lens of lights going down in another city.

Your play was simultaneously premiered on January 8, 2016 in theaters in Chicago, Toronto, Memphis and Charleston. Why?

Every talkback after every reading of early drafts of play never lasted less than an hour. Audiences of 40 or 50 were having conversations that went beyond this couple and their friends and family. I wanted to know if audiences outside of Chicago responded differently to the play. And they did.

For example, at the end of the play Celeste begins to lean into her faith and the fact that Laurel may not be spending eternity with her. Audiences in Chicago had no idea that Celeste loved Jesus that much. That was never, ever questioned in Memphis or Charleston or in Toronto. How could you not know that this woman loves Jesus? That prompted a few tweaks to the play.

How is producing this play with the Contemporary American Theater Festival different from other theaters where it’s been produced?

This show was launched with four creative teams doing full productions and three other creative teams gearing up for staged readings in their cities. My company was one of the ones producing it, plus, I played Jim in this production. CATF has been an exciting relief. I’m so excited to tell this story in a way that doesn’t feel like seven opening nights. Telling this story at CATF is a lot slower, and I’m loving it.

What was it like to play a character that you had written?

I act almost as frequently as I write, and I’m not sure there’s any other character I’ll feel as passionate about.

Your friend, Chelsea Marcantel says that her plays explore tribes. Do your plays explore a common theme?

Many of my plays are similar to Chelsea’s tribes in that they explore sub-cultures. I love digging into a sub-culture that people believe they know about and then upending their expectations.

That was true of the very first play I did in Chicago called Frat which was about upending the expectations of southern fraternities. My show 11:11 upends Christian camp counselors who accidentally drug themselves with Ecstasy. I upend expectations in Byhalia, too.

In your “Making Conversations” interview with Chelsea on her website, you said, “Whenever I start to sense that I have a style, I want to stop whatever that recurring style is.”

I spent about a year with Mary Hollis – one of the ensemble members of my production company, The New Colony – doing a play called The Warriors which was about the 1998 shooting at Westside Middle School in Jonesboro, Arkansas. Mary – 12 years old at the time – survived the shooting. It was a heavy docu-drama. Being able to follow that up with 5 Lesbians Eating a Quiche, an absurdist comedy, was one of my favorite moments as a playwright. I thought, “You can do whatever you need to do as an artist. You can write whatever you need to write. You don’t need to stick with what you just did that you’re happy with. Go ahead and do a 180. Write something completely different.”

In that spirit, I followed up 5 Lesbians Eating a Quiche with a drama called, The Bear Suit of Happiness about World War II soldiers putting on a drag show for the men in their camp.

In Chelsea Marcantel’ s play, Everything is Wonderful, Miri, one of the characters, says this: “I’d rather have anything I want than not want anything.” Would you rather have anything you want or not want anything? And why?

Not wanting anything.

Why?

Because that sounds lovely. A lot of unhappiness stems from what people do to each other in their quest to get what they want. You can, I suppose, change the world, but you always have to start with yourself. If you were able to get yourself to a place where you truly did not want anything – that person (whoever that is, whoever can achieve that, God love ‘em) would come from such a place of love and being present and listening to other people. To not want anything – what a great person that would be. That sounds lovely.

What’s the most outrageous thing you’ve ever done that you regret, but don’t tell me what it is. You’ve been commissioned to write a play about it. What’s the name of the play and what’s the first line?

The name of the play would be, The Interrogation. And the first line would be, “Speak up. We couldn’t hear you. Everybody’s listening. Go ahead.” The first title I thought of was The Execution, but then I thought, “No, that might keep away some ticket buyers.”