CATF: Why is this play called, The House on the Hill, and not something like, Long Day’s Journey into the Past?

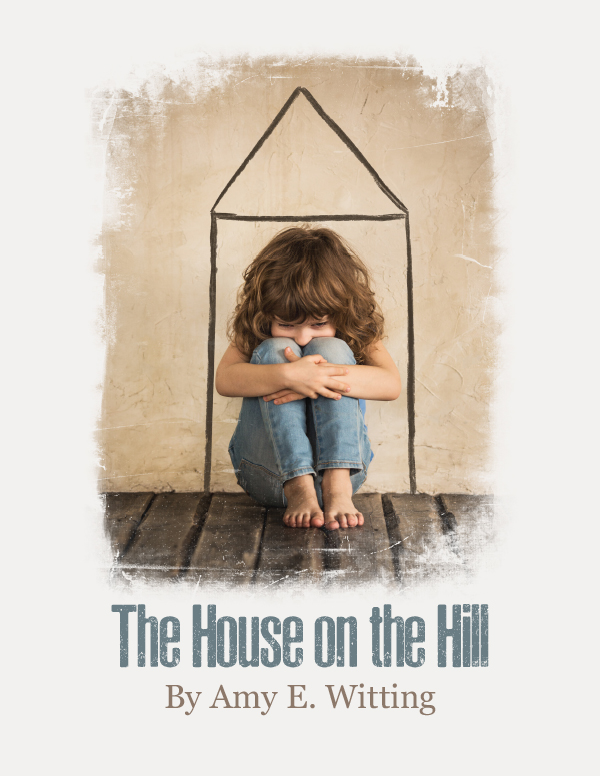

Amy E. Witting: The house is another character in the play. We all – I know I do – create containers for trauma. In this particular house, Alexandra has created a sanctuary in different compartments to hold the pain of a specific event she experienced.

Your notes for the play include a beautiful description of the role of the house. [Following are part of those notes:]

The House on the Hill is a container for all the pain and trauma Alexandra, or really we all, hold inside of ourselves. I believe we create shelters for ourselves to contain the emptiness and pain we can’t quite understand. In our own houses that we build we fill it with things to try and make sense of our own lives. What is a right-sized emotion for trauma? How can we protect ourselves but keep up an exterior image of who other people think we are? How did we get to where we are? What do we do with each of the rooms inside of us?

In other notes, you write that the house has a “heartbeat.”

This particular house is almost like another person. Alexandra and the house interact. She is able to interact with her emotional pain by creating a house that is comfortable for her. I think that there’s a way we kennel certain things after a particular loss to keep the memory alive.

In the past, one of my boyfriends – Charlie – passed away while he was in Ireland. I went to visit the house where he lived and this giant house felt so sad, like it had its own energy, its own feelings, and also contained pieces of him that we never talked about. I saw those little things and held onto them. We hold onto our pain to hold onto the memory of the person or the thing that we loved.

The reason I may have a lot of wisdom about trauma is that I experienced many deaths at a very young age. You can’t really talk about your own trauma until you sift through it and spend time processing it. Another boyfriend – Brandt – died in 2011 when he fell off a cliff in Africa. That death is specific to this play in that there was no chance of having a memorial because they weren’t able to bring his body back to America for a service. They brought back his ashes and we had a memorial here in Brooklyn. It felt like there wasn’t any closure at all.

The play explains why we need a place to go to mourn tremendous losses. Mourning Charlie, by being able to go to Ireland and visit a specific place and experience time with people who loved him felt, very different from mourning Brandt, who died while traveling in a foreign country traveling and then not having anywhere to go to mourn. I felt lost.

We don’t openly talk about our grief or we compare our pain with other people’s pain. In our current world especially, we’re living in a post-traumatic stress environment. I want my play to give people permission to talk about their pain and grief.

You preface your play with this quote from The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, “The loneliest moment in someone’s life is when they are watching their whole world fall apart, and all they can do is stare blankly.”

At some point in their life, everyone has a moment when they realize that their world is falling apart. Those moments are frozen in time. When I got the phone call that Charlie had died, I remember watching the world around me falling apart and realizing that my life was going to be different. I was paralyzed and didn’t really know what to do. It was years before I was able to stand on a solid foundation.

How did you survive grief? How do any of us survive grief?

My first defense was drinking a lot so I wouldn’t have to think about it. It helped me to move forward. Once that became an issue, I stopped drinking and then began a lot of self-care. Writing and therapy really helped.

The movie, Coco, shows how we need to talk about and remember people who have touched our lives and are no longer with us. It doesn’t matter how long we’ve known them or whatever our relationship was with them. If you feel pain about the loss, that pain is valid.

Is there any forgiveness in this play?

For Alexandra there is forgiveness of self throughout the play. At the end, she does come to a place of being open to the process of forgiveness. She becomes open to forgiving Frankie.

What is worse? Being a victim of childhood trauma or not being able to forgive childhood trauma?

They are equally as devastating. What I love about the journey of this play is that we get to see the love Alexandra and Frankie had for each other before the incident. Not only are they grappling with that loss, but they are also grappling with the loss of their relationship. After a trauma, you become a different person.

We have empathy for victims of an awful tragedy, but seldom for the perpetrator. We rarely put under the microscope the family of the perpetrator. Aren’t they victims, too?

I struggle with this a lot, because I like to think that we are all born from goodness; that we all have an opportunity for a second chance. During some readings of this play, I received a lot of strong criticism for having empathy for a particular character. But my question is, how can you not? We all come from the same place and to not be able to empathize with someone is a way of staying paralyzed in the grip of trauma.

Do you believe in evil?

Someone can commit an evil act, but I don’t think the heart of that person is evil. When I’ve meditated and written for the day and spiritually grounded and fit, my day is very pleasant and I encounter people in a way of love. But if I wake up and rush through my day, my life starts to unravel and I experience those same people in a different way. A person bumps into me, and I get angry and then that anger turns into something else. If the spirit isn’t being fed, then I think people can commit evil acts. We all have access to peace. That’s how we’re supposed to live. It’s an energy that’s outside of us.

Carl Jung said, “There’s no coming to life without pain.”

I can only speak for myself, but I don’t think I understand how to truly live until I experience profound trauma and pain.

In this play, you have adult characters literally passing their childhood characters. Why this theatrical device?

In one of the first drafts of the play the young version of the adults – young Frankie and young Alex – interacted with each other and the adults watched from the outside as the memory unfolded. Then I had a workshop at the Kennedy Center with director Bridget O’Leary of the New Repertory Theater in Boston, and she noticed that something about how these adult and childhood characters were interacting wasn’t clicking. She then pointed out that when I interact with my former boyfriend Charlie, I’m not interacting with him as if he was the age I am now. I’m interacting with the memory of him at a younger age. I’m also remembering myself at a younger age when I’m in that memory. So Bridget and I changed how the adult and childhood characters interacted and it all came together.

You wrote about a harrowing incident with an active shooter at Penn Station more than a year ago. At the end of your account you write, “We might not know the fear that is living inside all of us until we are faced with a stampede of strangers all running away from an imaginary bullet, but it is there, and I’m afraid if we keep living the way we are this fear is not going anywhere, and we will keep dropping our lives for the possibility of calamity.”

That was an eye-opening experience. After Charlie’s death, I lived like a victim of my stories, but that only brought on more pain and paralysis. I wasn’t moving forward with my own life. After the Penn Station incident, I don’t think, “Why me?” anymore.

The book, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk, includes a beautiful account about 9/11. A friend and a friend’s child witnessed people jumping from the World Trade Center. The next day, the child drew a picture of what he had seen that day. Next to the burning Trade Center is a giant trampoline so the next time people had to jump they could land on the trampoline instead. Children have an ability to process trauma, come up with a solution, and then move forward. As you get older, you process it in a different way. I was living in trauma for a long time until I learned that I don’t have to live that way anymore. That’s how my work has changed. At first my writing was about writing to heal myself, but now it is to heal others.

What’s it like to work with CATF?

Because the play is a bit polarizing, people were afraid to put it out there because it doesn’t follow a conventional dramatic arc – it’s a slow burn. Another playhouse even wanted me to change the memory, which I wasn’t willing to do. After the first conversation I had with Ed, I said to myself, “He gets this. This play found him.” At CATF, this play is being taken care of.

If you were going to write a play about your first memory, what would be the title?

Falling Out of The Car