CATF: You’ve said that your writing is inspired by “the hard truths.” What hard truths are in your play, Thirst?

C.A. Johnson: The hard truths are the ones buried beneath intersecting ideas, identities and people. Thirst puts a lot of people in motion and conflict and, inside of that motion and conflict, they bump up against things that are, to me, the real battles. Maybe Thirst is about politics, maybe it’s about gender, maybe it’s about special preferences, maybe it’s all of these things . . . or maybe, it’s just a play about how hard it is to let go.

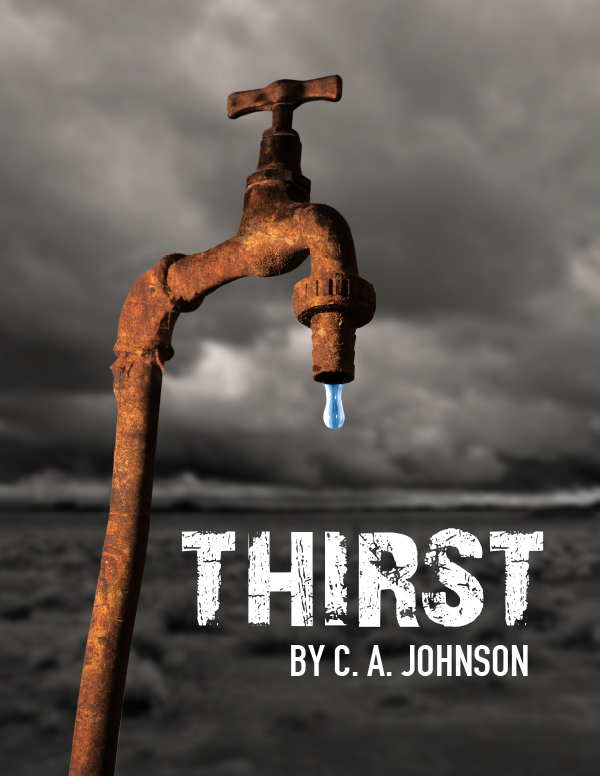

The very last line of W.H. Auden’s poem, First Things First is, “Thousands have lived without love, not one without water.”

We scrape by even in the direst of emotional straits, but if you don’t have the resources that keep you alive, that’s it. How do I raise the stakes in a play about the complexities of gender and race? How do I have that universal conversation in a way that reaches more people without giving them the out that they are simply inside the trappings of a very specific play? Without giving them permission to say, “Yes, I see that trauma, but I wouldn’t have experienced it because I am not a black woman from this place and this time.” But if you make the trauma about the most essential thing – the moment when you feel thirst – no version of you can say, “I’ve never felt that.”

About the water crisis in Cape Town South Africa, Guilio Boccaletti, the global managing director for water with the Nature Conservancy said, “Inequity plays out in water very obviously and what we’re seeing in Cape Town risks becoming an example of that. The social contract breaks down if the rich find their own solution and leave the rest to fend for themselves.”

A fellow playwright once sat in on a reading of Thirst, and afterwards said, “Imagine a world where a small sector of black men suddenly have power they can wield and they can wield that power for good.” We try to imagine futures in which we suddenly have power and would wield it in an unquestioning, loving way. But in Thirst these men aren’t doing that, or at least they are and failing for totally petty, personal reasons. Our own pain can corrupt the good in us.

Why is the moral center of this play a boy between the ages of 9 and 11?

Kids have brutal honesty because they haven’t learned how or why we sometimes hush the truth. They just say what they think. Some kids become what I call “super adult children” who have all the joy of a kid playing with a toy car, but are also constantly taking in the evils of the world and trying to translate them into something good. They are trying to blend what’s true about the cruelty of people with their childhood innocence. “Yes,” they say, “all those things are true, but the sun is coming up tomorrow.”

Kalil – the young boy in your play – says, “I know fightin’ ain’t good, but sometimes, not all the time, but sometimes . . . it’s necessary.” What are you willing to do to survive?

That’s something I think about a lot especially when I’m inside these plays. I’ve always said that I will be the best version of myself after I have children. I don’t know why I think that, but I know that sometimes when my mother looks at me, there’s this thing in her eyes that says, “Yeah, yeah, you – I would die for.”

In your artistic statement, you say, “I like to imagine the impossible in my work, those sublime moments when a woman discovers her own truth and finds herself suddenly bare before an audience.” Why is this impossible?

For a long time, the American theater was about large men with big dreams trying to conquer the world. Right beside them were the realistically resilient women who took care of everyone else but themselves. We don’t have enough plays yet where we can imagine what it’s like for a woman to take care of herself, although that’s shifted in the last half century. The strong black woman stereotype is complete bull and doesn’t allow that woman to be a person with interiority or anxiety or any of those things that make her normal or human. I want to write plays that give you some version of a woman’s strength and resilience that is true and not a stereotype. I want to show you the cracks and dare her to show them to you. The reason I call it impossible is because it’s been deemed impossible for so long, but the truth is that it’s very possible. We’ve known women our entire lives who are like that so why aren’t we seeing more of them?

What do you think of this perspective from Margaret Atwood?

“‘Why do men feel threatened by women?’ I asked a male friend of mine. … ‘They’re afraid women will laugh at them,’ he said. ‘Undercut their world view.’ … Then I asked some women students in a poetry seminar I was giving, ‘Why do women feel threatened by men?’ ‘They’re afraid of being killed,’ they said.”

Those comments are obviously spot-on. We are constantly in these conversations about where we’re headed and some of that is because for a long time we’ve been having legal conversations about parity and paid family leave . . . all these things that matter to women and mothers. These conversations are necessary and now so are big movements like MeToo. What does it mean when women say to men, “Here are the things that you’ve done to me.” It scares the crap out of men. I find it exciting and good because women have been terrified forever.

You yourself have taught teens. In your Medium article, Teaching Teens to Write: My Re-Education, you assign the following attributes to good writing: bravery, insanity, and humility. Regarding humility, you wrote that, “The writing room has no place for ego.” How does that square with your perspective in another Medium article, In Defense of Black Ego – “being a Black artist is inherently political, and necessarily a riot.”

There’s a reason why bravery, insanity, and humility are together – because you are constantly vacillating among the three. Ego lives between bravery and insanity; realizing the ridiculousness of saying, “I have thoughts, other people should hear them because what I have to say is special.” For me, a writing workshop is a microcosm of that transition between birthing a play and giving it to other human beings. That’s when the humility begins to play a part.

For black artists, so much of what you do means things that you don’t intend. So much of our narratives about black lives and black bodies and black people have been defined by people in power – mostly white people. When those narratives start to be drawn by black people themselves, there’s this constant negotiation, i.e., “That’s not exactly what I meant.” There’s this constant back and forth about who you are and why your intentions need to be restricted. Some artists are adept at playing that game and some artists have needed to play the game in order to get out what they need to say.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie writes brilliantly about feminism in a way that is so lovely, respectful and beautiful. Her book, Americanah, and her TED talk, The Danger of a Single Story, relate how women and people of color have been harmed by one narrative of how they should be. We need to hear that.

But we also need to hear a little of Kanye West who says, “I don’t need to do any of that. Take it or leave it.”

You have said that you write about what you know.

I write about home and what I know because I still have a lot of questions about that place, and I don’t do a very good job of asking those questions of myself. Through theater, through storytelling, I’m able to ask those questions. Playwriting for me is two parts therapy and one part, “Hey, I love this medium, and I love working out all my crap with a bunch of actors who have some of the same crap, and we share it with people who have a lot of the same crap.” When she was still teaching at Princeton, Toni Morrison started all of her writing workshops with, “Don’t write about what you know. Write something else.” I think you always come back to the things that you know, but you don’t have to do it intentionally if you don’t want to.

Audre Lorde said, “Art is not living. It is the use of living.”

We all agree to this pretense – especially in the theater – to sit in the dark in cushy seats with a bunch of strangers to watch a bunch of actors inhabit a fake story. In that moment of articulation, the actor shares the word that moves and the audience responds. We only get to experience that shared story-telling in the theater. Everybody is playing at a thing that is real and none of it is real, but the moment of sharing that fake thing – if the audience has agreed to receive it – is totally real and alive – it is living. That’s what I’m after.

What’s it like to work with CATF?

One summer when I was still in high school, my best friend’s mom told us about a theater festival in Shepherdstown, so we hopped on a bus and in the morning, saw

Lidless by Frances Ya-Chu Cowhig and later that day, saw White People by J.T. Rogers. I knew then that I wanted to be a playwright. When Ed Herendeen and I connected on the phone about Thirst, he was so open to what I saw in the play and what it could mean to other people. It’s not simply a play to see and then go home. It’s a play to see and continue a conversation. Ed saw that. It’s not true of a lot of theaters, especially in New York.

If you were going to write a play about your first memory, what would be the title?

Bare Feet.