Researched, interviewed and edited by Sharon J. Anderson, CATF Trustee/Professional Story Listener and Creative Director www.sharonjanderson.com

CATF: Your play begins with a couple of epigraphs. The first one is part of a poem by Willa Cather called Prairie Spring. The opening of the poem describes the prairie landscape in almost funereal terms, then “youth” bursts into the scene with its “fierce necessity” and “sharp desire.”

AG: When we are young, everything has an edge to it. We look for the edges, try to scale them, and fall off all the time. I love the imagery of this particular quote because fairly recently I went through the teens with my own two teens. I remember how that felt. There was no proportion to life. Everything felt hugely mundane or massively incomparable or insanely wrong.

Your other epigraph is from the song, Wild Horses by the Rolling Stones: “I have my freedom, but I don’t have much time.”

As an adult, you realize how quickly everything goes. All of a sudden, the bulk of your life is behind you and you’re like, “What? That was just yesterday!” Teens do not have enough time for anything. They don’t have enough time to make the world better, their lives better, or their bedrooms better.

You often talk about how your kids brought you to your knees. Did you ever bring your parents to their knees?

Yes, very much so. I was a good girl, but my family – like many families – had a lot of secrets, and a lot of misinformation and missing information. In my middle school years, I started to rebel against it. I didn’t know that that was what I was doing. I just did it.

As a parent myself now, every time I discipline my kids or enforce any kind of punishment, I look in my rearview mirror and ask, “How would I have responded to that?” which is sometimes helpful and sometimes completely debilitating. Sometimes you just have to act. In some of their responses to my rebelling, my parents probably fostered even more misbehavior. I don’t know if there was a good way out. I don’t know if what I went through could have been avoided.

Willa Cather also said, “People are always talking about the joys of youth – but, oh, how youth can suffer!”

Gosh, yes. It’s insufferable. I don’t know anyone who wants to go back to that time. It’s impossible to be a teenager, and I don’t mean just today. I mean in the scheme of life. It’s hard because you have so much desire. You have so many needs, and you have so little power.

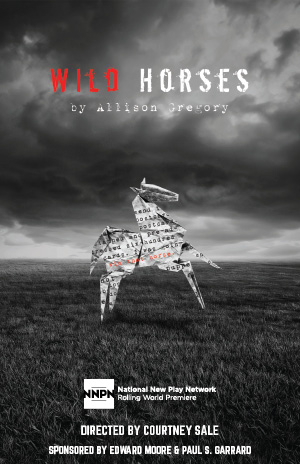

I wrote Wild Horses because I watched this struggle with my own kids who are in a very different dynamic than I was growing up in terms of our family life, what’s going on in the world, and their level of privilege. But it doesn’t matter. Being a teenager is hard. I wouldn’t wish it on anyone.

This play is about a baby boomer looking back on her youth. Why look back? Does looking back heal teenage trauma?

Writing forward can certainly heal. I wasn’t in any great pain about my own period of adolescence, but watching what my kids were going through, waking up in their skin – that itchy skin of adolescence – made me uncomfortable and anxious.

I started out writing a completely different play, a play about a mother giving driving lessons to her daughter, a play about a mother trying to break through to her daughter to find the person who was so covered.

Not Medea was my failed one-woman play. I didn’t think Wild Horses was going to be my one-woman play because it began with these two characters. But as I wrote it, it started going in a different direction. We were going back further than driving, and at some point I realized that it was this woman’s memory. It’s not my memory. I wouldn’t even call it a memory play. It’s a reliving for this woman, a very visceral reliving for her.

Why one actress playing eleven characters? This is not a monologue. This is a monopoly-logue.

I wanted to activate the play. Having one character tell us a story could only take us so far. We could only listen for so long. When I started bringing in the other voices, it was a matter of, “Do I want to bring eleven actors on stage? Can this story hold that?” I wanted to keep the story feeling more intimate.

Isn’t it risky to have one actor playing eleven characters?

This is definitely an experiment, and it’s a risky one. Not Medea was a challenging role. This one is also challenging, but in a very different way. It’s almost more performing than acting. It asks an enormous amount of the actress who plays the part. It’s exciting for the audience to watch this person change. That pulls us into the story more than if someone walked onto the stage and walked off. Or more than if she put on a hat and a jacket and became Cousin Dirk. She’s changing internally right before our eyes which makes the play gallop.

In her book, Extreme Exposure: An Anthology of Solo Performance Text from the Twentieth Century, Jo Bonney writes that the key to solo work “is to bring the audience up onto the stage and into the scene with you. It is they who must give you even more than you give them in the way of imagination and creative power.”

That is spot on, and that is what we aspire to do with this particular play and production. I’m so excited about the set design because it’s going to make the audience step into the world of the play the moment they step in from the outside world and across the threshold of the theater. It will be a great experience for the audience and the actress because it will bring the play more into her proximity, both figuratively and literally.

The music in this play seems like another character.

The music plays a huge part both in setting the scene and in the way it can articulate feelings that nothing else can. I am so envious of musicians and songwriters because music imprints on us certain feelings and more importantly, certain times in our lives.

Nearly all of the music in this play is from the early 1970’s, what Tom Wolfe called, the “me decade.” Is that why you chose this time period?

Any decade can be called the “me decade,” really. Perhaps it was the first “me decade,” and there were subsequent “me decades.” I love the music of the seventies. So does my daughter. There’s something about that music that invited us in; that told stories in a way that I could really listen and relate to – so much heartbreak, longing, and yearning.

At one point in the play, the dad says, “Horses come back; they know where home is.”

Horses are just magical. They run in slow motion, just like a gazelle, though they’re bigger. They’re 1,200-pound ballerinas. They have all this power, but their biggest, most upfront instinct is fear which plays against their muscular, graceful, strong exterior.

Horses obey 8-year-old girls who are as thin as a stick. Don’t horses know that that tiny thing on the back of them could fall off and they could jump that fence and just go? They are not leadership animals. They are receptive animals.

“We weren’t freedom fighters, we were freedom takers” is a powerful line in this play.

These characters didn’t have much power. They aren’t being taken seriously, so it’s up to them to create their own agency. By living their lives the way they did, they weren’t going to be given freedom, so they took it in whatever way they could, whether that was stealing those horses and setting them free or driving a car when they are only 13 years old.

Society says to teenagers, “No you can’t. No you may not.” We don’t give teenagers much credit at all. A teenager has to be an Eagle Scout or something before he or she will be listened to. Part of that is because teenagers are crazy. They are all impulse and appetite. It takes too long to earn an Eagle Scout badge. If you see a wrong as a teenager, you want to go out and make it right immediately however you think it should be done. It’s not always the best way, but it’s a way.

How’s it feel to have plays two years in a row at CATF?

I am just over the moon, ecstatic and as surprised as anyone. I had such a great experience with Not Medea, with the rehearsal process, production, and wonderful audience receptions. It was such a great deal, I hoped to have another play at CATF sometime down the road. I never thought it would be the following year. That I’m in the mix is a happy accident and I’m thrilled.

In Chelsea Marcantel’s play, Everything is Wonderful, Miri, one of the characters, says this: “I’d rather have anything I want than not want anything.” Would you rather have anything you want or not want anything? And why?

There’s a sadness to both. It’s very Zen to not want anything, but part of being human is desire, and that problem is what we build our lives around. If you remove that desire, if you remove that want, we remove an essential part of the problem we’re put in the world for which is to solve our wants. We’re not supposed to be perfect.

There’s a danger in having anything you want, which makes for an interesting play. In a play, the best answer is Door #1 – have anything you want because that is loaded with all sorts of problems.

What’s the most outrageous thing you’ve ever done that you regret, but don’t tell me what it is. You’ve been commissioned to write a play about it. What’s the name of the play and what’s the first line?

The first line of the play is, “We shouldn’t be doing this,” and the name of the play is, That Night in April 1988.