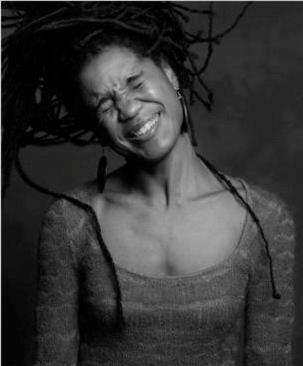

Chisa! (Part Two)

PART TWO: Researched, interviewed, and edited by Sharon J. Anderson, CATF Trustee/Professional Storyteller. READ PART ONE OF THE INTERVIEW HERE.

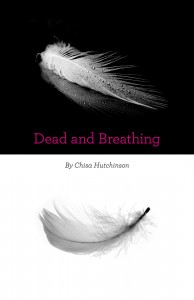

CATF: In his book The Savage God (written after the suicide of his good friend, poet Sylvia Plath), A. Alvarez describes suicide as, “ . . . a closed world with its own irresistible logic.” Is “Dead and Breathing” a closed world with its own irresistible logic?

CHISA: Yes, I think so because it departs from conventional ideas of morality. It’s not necessarily about what’s right and what’s wrong, but rather what’s beneficial and what’s not. I think it’s definitely a world of its own, but one that I hope is still intriguing for folks to visit for an hour and a half.

CATF: I read that one of the things that inspired you to write plays was a debate you heard between August Wilson and Robert Brustein about color-blind casting. I once saw a scene from the play, ‘Night, Mother by Marsha Norman – about a daughter announcing to her mother that she plans to commit suicide – with two white actresses, and then saw the same scene with two black actresses. The two scenes felt very different to me.

CHISA: They should feel different! The black actresses add a whole other dimension. I felt that way when I saw, “A Streetcar Named Desire” on Broadway with multi-racial casting. When the sisters are talking about their struggles and struggling in the South, it takes on a whole other meaning. When you cast a black actor in a role that is traditionally white, of course it’s going to “color” it differently just because of our cultural baggage which can, actually, heighten the dramatic narrative. It can certainly refresh it.

I also think, though, that it can hurt the actor. Having been in the position of playing a white character, it’s hard to fully commit to a role that you know wasn’t really meant for you. You’re constantly thinking, “I wonder how the audience is feeling about this? Are they taking this differently than the way it was intended?” Black actors should have the option of getting their own narratives out there; to play a role that was actually intended for a black actor, otherwise it’s going to be intellectual acrobatics throughout the audience. That is, people will be focused on figuring out what statement the director is trying to make by casting a black chick in this role. I think it does a disservice.

CATF: Would it do a disservice to “Dead and Breathing” if it featured two white actresses?

CHISA: To an extent, yes. There are elements in the play that are distinctly African-American, and I think that they would either be lost entirely or take on a whole different meaning if they were performed by non-black actresses. Not that I’m not open to that, but it is a different interpretation. As a playwright you have to accept that people are going to take liberties. You try your best to make the blueprint as clear as possible, but people may have trouble casting the eight black people and the one white person; they’ll have to use a couch instead of a bed, and so forth.

CATF: You have said that you write plays to “make yourself and others like you more visible”. Why do you need to make yourself more visible?

CHISA: Why the hell not? If I see one more damn play about a white chick who is restless in her marriage . . . please, just get a divorce and be done with it so I can go home.

African-American culture? It doesn’t get more dramatic than our experience. It just doesn’t. If you want to put something electric on stage, put black people on stage. First, we have very interesting experiences that go beyond self-indulgent fluff that I really can’t get into. Enough already with the whining. If you want a play that’s about something bigger, a play about people who struggled mightily with something beyond themselves, put black people on stage. Second, I think about audiences. I’ve had former students email me out of the blue to thank me for the race-appropriate monologue they performed in my theater class; how it inspired them. There’s something motivating, too, about seeing yourself on stage, about seeing yourself in art. It’s incredibly validating. It’s not just a fluffy, fun experience. When you feel important enough for someone to make art about you, you are motivated to go out and achieve something and contribute to the world.

CATF: Is that the singular, peculiar, unique thing about art?

CHISA: I think so. People for whom going to the theater is a regular Sunday afternoon and who regularly see themselves on stage – those people begin to take this art for granted. For others it is a relatively new thing, “What? There are black people on stage? There are Asian theater companies out there?” For people for whom this type of theater is different . . . they can feel it and appreciate it in a way that may be lost on others who’ve been able to take it for granted.

Some people are going to be shocked and scandalized by the ending to “Dead and Breathing”, but I was not shocked, and I did not write the ending to scandalize anyone. Perhaps I am taking the dramatic narrative for granted.

CATF: Why even take the risk of scandalizing an audience?

CHISA: Again, I honestly did not set out to scandalize the audience. I just didn’t. For me, it is what it is. That’s all I can say about it.

CATF: Alice Walker said that, “Life is better than death because it’s a lot less boring and it has fresh peaches in it.”

CHISA: I would have said mangoes.

CATF: You have said that this line from the poet, Mary Oliver is “everything”: “There are so many stories more beautiful than answers.” Why is this line, “everything”?

CHISA: Whenever anyone asks me a question, I can only answer in stories. The questions and answers that delight me the most are stories. It’s the way we connect to each other as humans. Stories are the best way for us to make sense of anything. Sharing our stories literally is everything.

CATF: What’s your story, Chisa?

CHISA: I came. I wrote. I conquered.