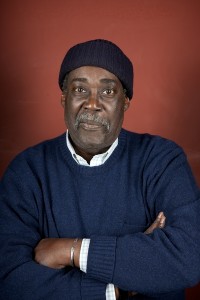

Charles Fuller Discusses ‘One Night’

Researched, interviewed, and edited by Sharon J. Anderson, CATF Trustee/Professional Storyteller

CATF: What was the most important thing the military taught you?

CHARLES FULLER: I enlisted in 1959 and was there until 1962. While there, I had the opportunity to read all the great works in English. I had an opportunity, in a sense, to finish college. I had left Villanova my junior year because I wasn’t happy. My father had two jobs to keep me in college, and I thought that was a waste of his money, so I left. In those days, you couldn’t sit around your parents’ house; the next best thing to do was to join the military, so I joined the Army.

CATF: Your experience in the military was essentially a good one?

FULLER: Yes, but it is profoundly disturbing to see the kinds of things that are happening in the military at the moment – these extraordinary charges of sexual assault. This was probably going on when I was in the military but at the time, there was no large female population.

CATF: What convinced you to give a voice to women who have been sexually assaulted?

FULLER: This may sound naïve, but sexual assault is simply wrong. You can’t keep brushing things under the rug and believe they will suddenly disappear. You can’t keep maintaining that all the male soldiers who came home were heroes when last year the estimate of sexual assaults was 26,000.

I didn’t start writing to tell happy, little stories. I started writing to make some impact on the world in which I live. If you don’t want to say anything about sexual assault, that’s your business, but I want to say something about it. I think it is absolutely and unequivocally wrong. We have no right because we are in the military to rape fellow soldiers who just happen to be females. A lot of victims are male as well. In the Army I was in, the life of the person next to you was as valuable as your own. You would never do anything to hurt your comrade. Your life depended on him, and in the case of Iraq, those gentlemen’s lives depended on the women they were raping. It’s horrifying.

CATF: Why is war hell?

FULLER: Because it’s justifiable murder. The idea that the only way we can change things or convince people or defend religions or overthrow governments — whatever those reasons for starting wars — the idea that the only way we can do that is to kill one another is horrible. It’s horrible because there’s a kind of acceptance; a kind of behavior that maintains that during certain operations we can and must kill one another in order to succeed. That’s absolutely insane.

CATF: Does war corrupt the military?

FULLER: I’m not sure about that. What happens is this: when we come to believe that the only way to make change is to murder one another, the idea of “the other” makes less valuable the human life it possesses. As a consequence, we can kill the “other” and not feel guilty. Unfortunately, human beings spend too much time rationalizing that war is right under certain circumstances; that it’s okay to threaten and kill other human beings.

CATF: You have said, “Plays are about language”. The military today trains soldiers to “neutralize” and not to “kill”. Does the military dehumanize people?

FULLER: I don’t think so, but over time the language of war has changed. When I joined the Army in 1959, we learned how to “kill” the enemy. When I was a kid, a person was “homeless” and a guy without a job was called a “bum”. When is the last time you heard that term used in current language? Language has changed over the years, and that’s reasonable. To be concerned about another person’s feelings despite what they are or what they are involved in is okay. CATF: You have said, “sexual assault in the military is now academic”.

FULLER: It is something that is accepted. What I find very strange is that we haven’t worked out a way to do very much about it. The bill that was going through Congress at one time was not passed because it would take some power away from commanding officers. To solve this problem, we have to bring people who are accused of sexual assault into civilian counts.

CATF: What do you think about the recent increase in rape scenes on TV?

FULLER: I don’t know what the heck is going on with that. Most of those scenes are extremely poorly done and seem done only so viewers have something to talk about at work the next day. If you’re not serious about doing something about rape, you shouldn’t even think about writing about it. After a rape scene, you have to see that someone is punished; that they are made, in some way, responsible for what happened. It is not something to laugh about, it not something to dismiss. That kind of behavior is not entertaining. It dehumanizes women. It’s horrible.

CATF: Thirty minutes before this interview began, the Washington Post published an article entitled, “Jurors to weigh whether ex-Marine should be executed”. [LINK TO ARTICLE HERE] The convicted Marine attacked a soldier – at random — wrapped her neck with the power cord of her pink laptop and sexually assaulted her until she was dead. Should this ex-Marine be executed?

FULLER: I don’t believe in the death penalty. People should be isolated from other human beings. That’s enough punishment – isolated for the rest of their lives.

[Charles Fuller “in conversation” with Ed Herendeen during the 2014 Season Annoucement, Part One.]

[Click for Part Two, Part Three, Part Four, and Part Five]

CATF: About America and Americans, you have said, “calamities seem to bring us together but we discard things quickly”. Are we discarding women in the military?

FULLER: Today, a strong, religiously evangelical tint seems to be growing in the military. Yes, there is respect for women, but women are considered less than men. The more religion enters into the military, the more this happens. When I was in the military, I don’t recall any evangelical preachers trying to change things or baptize people. I saw chaplains who would talk to you and help you through difficult times. Today? I recently read of the extraordinary increase in the number of evangelical preachers and congregations growing in the military. Some of the precepts of evangelicals who believe in the strong translation of the Bible are that women have very little place aside from being helpmeets to men. I also think some people don’t want women in the military at all because it equalizes you. That’s dangerous to men because they believe they are stronger and more important than women.

CATF: There is a blues song called, “Mean Old World”. [LISTEN TO THE SONG ON YOUTUBE] Do we live in a mean world?

FULLER: The world is a product of human beings, and we can change the world. The world is not, in and of itself, mean. It’s just what it is. We have made it whatever it is — we cannot blame it on wildness or Mother Nature. We have destroyed whatever was good. To say that the world is “mean” is to not understand our place in it or to not understand what we have done to it. The world was not mean when it was created and if it is mean now, we have made it mean because the meaning of mean is something we describe.

CATF: You have such a peaceful presence, but you can write a visceral play like, ‘One Night’. Did writing it help you dissipate your anger about sexual assault?

CATF: You have such a peaceful presence, but you can write a visceral play like, ‘One Night’. Did writing it help you dissipate your anger about sexual assault?

FULLER: Every day, I confront things that upset me, that I think are wrong, that don’t make sense. But the only way we can deal with them is rationally. You can’t write “crazy” things. Art is about framing. A picture that encompasses the whole world is one that has no frame. How can you know what it’s about? The best art is framed. Books are framed from cover to cover. Plays are framed by where they begin and where they end.

Art is something you must think about in terms of how much you do and whether or not what you do is sufficient for the idea or the anger that you have. You can’t do that irrationally. If you do, your art is irrational, and no one will understand it.

CATF: Has your art healed you?

FULLER: Sometimes.

CATF: Should art heal?

FULLER: It can suggest ways of healing. The weatherman knows which way the wind is blowing, and that’s what art can suggest for us. Where is the weather vane turning? What direction? I have no idea whether or not art can overcome evil, but it can suggest that maybe we need to think more about an issue. I don’t think art can win wars. I don’t think art can overturn nations. But art can tell us which way the wind is blowing and that just might help us to better understand the world in which we live.