Meet Donja R. Love

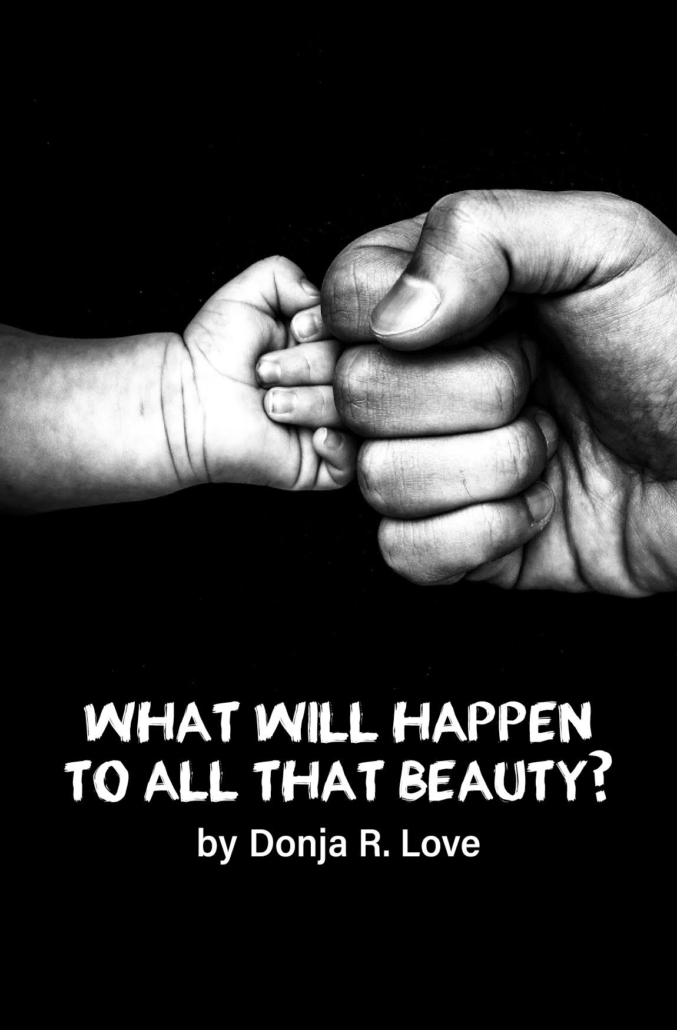

Donja R. Love (any pronoun said with respect) is Black, Queer, living with HIV, and thriving. They’re the founding executive director of Write It Out! – a playwright’s program, prize, and retreat for people living with HIV. They’ve graced the cover of POZ Magazine’s POZ 100 issue, A&U Magazine, and Positively Aware. They’re one of Plus Magazine’s “Most Amazing People Living with HIV.” They’re the recipient of POZ’s Best in Performing Arts Award, the Horton Foote Playwriting Award, the Terrance McNally Award, the Antonyo’s inaugural Langston Hughes Award, the Helen Merrill Award, the Laurents/Hatcher Award, and the Princess Grace Playwriting Award. Other honors include the Philadelphia Adult Grand Slam Poetry Championship. Plays include soft (MCC), one in two (The New Group), Fireflies (Atlantic Theater Company), Sugar in Our Wounds (Manhattan Theatre Club), The Trade, and What Will Happen to All That Beauty? They’re also the co-founder of The Each-Other Project, a digital media platform that celebrates and fosters community through art and activism for Black queer and trans communities, through which they’ve produced numerous short films and digital series. Visit: www.letswriteitout.com & www.theeachotherproject.com.

Interview with the Playwright

Conducted and edited by Sharon J. Anderson

Why do you call this play, “an offering?”

This play is my attempt to offer representation to Black people with HIV and to those black people who have died due to AIDS-related complications. But it is not just an offer for visibility and representation, but also for softness, beauty, and love to my community. Because I believe so deeply that the work I do as an artist and writer is spiritual, I would be doing this piece a huge disservice to categorize it as simply a play. In my studies and in my love of theater, I’ve never really seen black people represented in such a way that holds space for a family over the course of 30 years as it navigates AIDS and HIV.

Those 30 years are from 1986 to 2016. Why did you go back in time?

I deeply believe in intergenerational relationships, and I’ve been so blessed to have friends who survived the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. While hearing their stories and holding space with them as they shared their experiences, what I would often hear is, “No one ever wanted to hear my story. I never had the opportunity to share what happened to me.” Also, Black-queer-bisexual-transgender-loving men have the highest AIDS contractual rates. One in every two Black gay men are projected to be diagnosed HIV in their lifetime. That a group of people at the height of the AIDS epidemic felt so erased and never had an opportunity to share their stories, made me feel as a dramatist that it was my obligation to craft a story of a world where they were able to see themselves reflected and to also bring it to where we are today. Granted, Part Two takes place in 2016, but you are still able to see the scope and breadth of what it was like to navigate AIDS and HIV in the 1980s. You can see what has changed, and unfortunately, what looks exactly the same.

Why is it important for patrons to see both parts?

The offering exists as one. We are experiencing a family over the course of 30 years. In Part One, we experience what it was like in the past for a father. In Part Two, we experience what it is like for his son and how these two unknowingly have this connection. Families are cyclical and always continue to evolve and grow. It is important to experience both parts to witness the evolution within this family.

Your play includes several tender and sensual love scenes. James Baldwin has said, “To be sensual, I think, is to respect and rejoice in the force of life, of life itself, and to be present in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of bread.”

Oh wow, that is a connection if I ever heard one. So often we deny ourselves pleasure, whether that is sensual pleasure with another human being, or pleasure in being with yourself on a walk or hike. We have conditioned ourselves to believe that we don’t deserve pleasure; that we have to actually do something to earn pleasure. That something is normally work rooted in capitalism. We all deserve pleasure in life and have been conditioned to think that pleasure looks one way. No, pleasure is a multitude of things.

The breaking of bread is for me rooted in the ability to hold space with individuals and say that we are in this thing together. It is holding space that allows us to ask, “What are we experiencing together? What is my point of view of what we have witnessed? What is your point of view? Where do we meet in the middle?”

“Soft” is a pivotal adjective in your vocabulary. It’s almost like a verbal tick.

Absolutely. Friends once named me, “the grandfather of softness” because of how often I talk about softness. For me, softness is very much an act and a state of being. When you exist within marginalized identities – whatever those identities might be – the world can be incredibly hard. So if this world is being hard on us, why do I want to add onto that? Why do I want to be hard on myself? I have it within me to exercise softness, at least to myself. If I start with me, hopefully, I’ll get to a point when I can exercise that softness in the community so other folks can experience it as well.

How much is that softness connected to your parents?

It’s foundational. My parents met each other when my dad was 16 and my mom was 15. A year later, I was born when my mom was 16 and my dad was 17. They have been together ever since. The amount of love that they gave to me and my sister and two brothers is something so phenomenal. I must hold space for it. Think about it: by the time my mom was 19 and my dad was 20, they had three kids. I’m in awe of the light and love they were able to cultivate as teenage parents.

When you came out to your parents, your mother said, “As a parent, all you want is for your child to live an easy life, but you won’t, your life will be hard because there are millions of people in this world who don’t even know you and want you dead.”

I remember that like it was yesterday. I told her before going to work at a retail store and the whole time I was there, I thought about what we would be talking about when I got home. Of course, my mom shared this with my dad, and when I got home, they both wanted to share space with me.

My dad handed me a Bible open to a particular verse – and to this day, I cannot remember what the verse was – and he asked me to read the verse out loud. After reading it, he asked me, “Do you know why I had you read that?” I thought, “You had me read that because I’m not supposed to be gay, it’s an abomination, I’m going to hell”– all these things that we have been indoctrinated to believe. But my dad said, “I wanted you to read this verse because there will be so many people who will use the Bible against you. I want you to be equipped in your spirituality and to know that you are divine. The Bible is not a weapon to be used against you. Who you are is beautiful and the Creator, God, made you just who you are.

How do we exercise softness?

That’s a lot of work. Too many folks exist in a space of ignorance because they live in a bubble. When they meet people who exist outside of their bubble, they have to recalibrate out of fear. Softness for me means to have patience. It means grace and vulnerability. I fail quite often, but I pick myself back up and continue to stay rooted in softness as much as I can. We will always encounter situations that are difficult. How will we rise in those moments? It will always be different.

Your play begins with this epigraph from The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin: “I wondered, when all that vengeance was achieved, what will happen to all that beauty?” What vengeance?

This Baldwin essay is about racism and what happens to Black folks when they experience racism and exert vengeance and pressure on oppressors. If we had the opportunity to exist as the fullest version of ourselves, if we had the opportunity to end our oppression, to eradicate the shame we’ve been conditioned to hold onto, what would happen to all the beauty of us just being able to be ourselves? If we were able to release that weight, who would we be? What beauty would we occupy? What will happen then?

If you had one piece of advice about life for a loved one, what would it be?

Dr. Maya Angelou said that the best advice she ever gave was to her son when he was younger. It was so simple and so intimate: “You have to have a place within you that is so pristine that you do not invite anyone into that space.” You are the only one allowed into that space because that is the space where you are able to access the divine, the great I am. So if you are struggling and need clarity, go into that space where you have allowed no one in but you and the great I am, and have a conversation with yourself about how to hold only yourself and who are you in this moment. For me, this is a guiding post in softness and divinity and holding onto oneself.

What question do you wish an interviewer would ask you?

I can’t think of one. I guess I’m content with what I’m asked. Thank you for making space.

What image immediately comes to mind when I say the word, “love?”

Instantly, my mom. My mom is the first embodiment of love. When I think about my mom, I think, “Wow, at age 16, you were literally home for me for nine months. You did everything you possibly could to make sure for nine months that you were the best home I had.” So, my mom is the first person that comes to mind when I think about the word, “love” because she’s a foundation for me.

What image comes to mind when I say the word, “family?”

I think about my husband. We’ve been having many serious conversations about starting a family and what that would look like for us. As queer persons, we have so many possibilities of models for what love can look like when building a life with someone of the same sex.