Meet Harmon dot aut

Harmon dot aut (they/she)

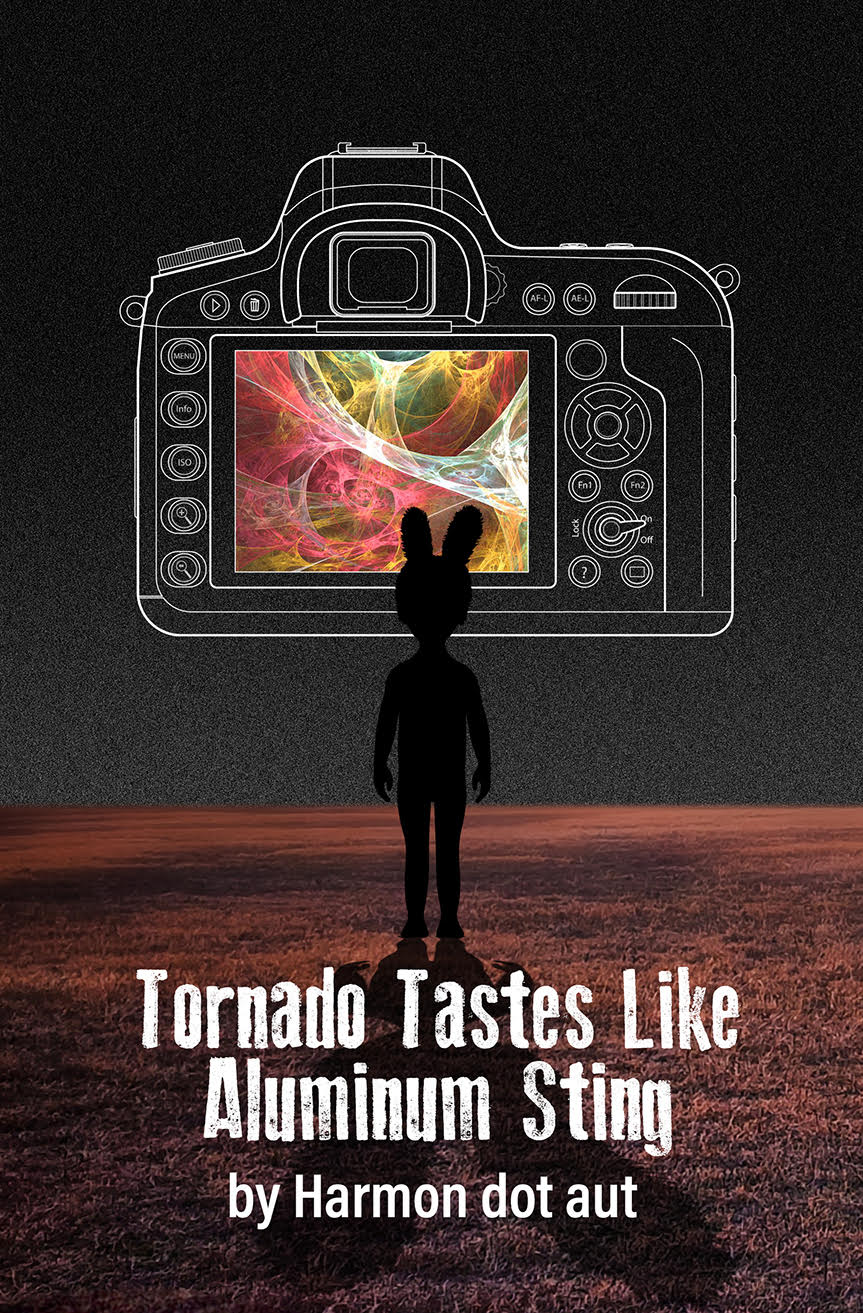

Harmon is a non-binary, (dis)abled, Autistic PneumaFractalist. Writer, Filmmaker, Singer/Songwriter, Actor, Visual Artist. An excerpt from Harmon’s play, SPACE, appears in the anthology: WE/US: Monologues for Gender Minority Characters – Smith & Kraus, March 2023. Recipient of the 2023 Venturous Playwright Fellowship (PWC) for Tornado Tastes Like Aluminum Sting.

Selected works include: Naming Things & Space (STE 2022); Minden (Reading @The Tank NYC), People Like Us, a new musical (written with the film composer & singer/songwriter Lisbeth Scott, in development); No Land to Land In (Dixon Place, Director: Craig Lucas); Goodbye Kansas, a new musical (KC Fringe Fest); Disability Romp Ballet (A Ha! Dance Theatre, Folly Theatre, KCMO).

Harmon is a fellow at the Hermitage Artist’s Retreat in Englewood, Florida and a recipient of a Visionary Playwright Award, TheatreMasters, NYC. Harmon was a founding member of the notorious gay sketch comedy troupe, Hot Dish! Harmon began creating tactile paintings, embroidered sculptures, and soundscapes in their youth “when my voice turned off.” Harmon lives with their husband in Hudson Valley, NY. Current Projects in Development: Untitled Mystery Series, DramaDeluxeKenya. A hybrid documentary with LostNationsPictures called Commercials for God.

Interview with the Playwright

Conducted and edited by Sharon J. Anderson

Tornado Tastes Like Aluminum Sting is a title that touches many senses and faculties, but is very puzzling. How would you describe your play?

I would describe it as a play about a family who loves each other. That is the core of this play, and love was the most important part in writing it.

Did you write this play so others could understand more of who you are and what your world is like?

I actually did write this play for us – for autists like me. It’s an invitation to everyone. Chantal [the child in the play] presents it that way. But I wanted to write a play that in a way privileged our processing and our way of thinking because it isn’t in much of any dramaturgy when I go to the theater.

You have said, “I really trust that audiences are hungry for anything that’s new; anything that is human.” Why do you trust that?

It’s partly a natural positivity that I’ve always had. I used to call it, the “F.U. Spark.” It kept me going as a child – that little engine of belief, happiness, and joy. I am a little older, so it’s taken me longer to get here, but we need each other, particularly in the divisive time we are living in. We have to have some grace with each other.

You have described the “F. U. Spark,” as that “piece of me, deep inside, that made it through all the violence, the part that no one could extinguish. We’ve all got it.”

This is in relationship to the documentary that is being made by James Rutenbeck [Lost Nations Pictures] featuring my life and work, and is particularly in reference to my experience of growing up in rural Kansas. Each of us who is different experiences all kinds of abuse. I could not walk down the street by myself without being threatened. But somehow there was still a skip in me, a fizzy part of me that no one could penetrate. I feel blessed that I had it and still have it.

Is this play based on your life?

It is not an autobiographical play. I did give Chantal some of my conditions: I am autistic, I am nonbinary, I do have synesthesia, and I did grow up in rural Kansas. Those attributes and the landscape, yes. The rest of it, no.

Is this play about the childhood you wish you had had?

One reason I wrote it was to write parents who were accepting. They accept Chantal’s differences the way someone would accept a different hair color. They are just like anyone else. They are messy, they make a lot of mistakes. They are very human.

Film in your play is a significant way Chantal processes their experiences.

I love film. It does a couple things. A lot of autistic and ADHD kids have hyper-interests and will go on and on about those interests. There’s a lot of info dumping. Also, Chantal explicates what confuses them through the lens of those films. They are trying to find a relationship.

You call yourself a “PneumaFractualist” – “I don’t have a language-first brain. In my mind, numbers and shapes, swirling colors, and millions of scattered flakes that resemble crayon shavings are the data I process. My memories, for example, are embedded in these three-dimensional objects. Accessing the matching words with the shapes is akin to kneeling on the floor with presbyopic eyes and trying to pick glitter out of the carpet.”

Talking doesn’t feel natural. It takes a lot of work just to speak. I don’t understand the mechanism, so when I am talking to you, it’s not like it’s automatic. I’m constantly thinking about it and working to put the words in order. I don’t see words because I see images in my head and have to translate the images into the words and speak. When I was a kid, I learned that if I could imagine a grid floating in front of my vision, then I could focus on one little cell at a time and block the rest out. It’s a kind of meditation. I taught myself just to focus on that information alone. In doing so, that’s when I realized that there are such big worlds in such small details.

Does one color or shape always represent the same feeling?

Yes, it’s consistent. The difficulty for me is that because all of my senses are affected that it sometimes becomes incredibly difficult for me to know where its coming from. If I have that grid and can get it really small, I can understand. When I look at my husband’s roses outside, I zoom on one and they always sound like a different bell ringing. If I look at all of them, it sounds like this bell chorus. Sometimes it’s magnificent, sometimes it’s a lot!

Do you have any formal training?

I don’t. My mother would go to thrift stores because we didn’t have any money and come home with boxes full of books. I would go through them and gave myself the most eclectic education. I read text books, religious books, geometry, intro to calculus, American history, Norton Anthologies. I discovered plays that way. The first two plays I ever read were, Julius Caesar and For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf by ntozake shange. I read them until the pages fell out. I didn’t understand them. That became my education. And they were poetry.

In your play, Chantal quotes lines from “Death Fugue,” a poem by Paul Celan, the most famous of Holocaust poets. Celan’s poetry has been described as exhibiting a “complicated and cryptic style that deviates from poetic conventions.” Is this what drew you to his poetry?

Yes, and there are many writers who are complicated and cryptic, Hart Crane being one. I think it’s because I had to read it over and over and over and over and over again to understand what was in the gap. Because words were not my first language, I was always trying to read the gaps. And I read poetry because I think, like Hannah Arendt, to learn about our history you always go to the poets.

About your play, the playwright Craig Lucas said, “For me it is akin to the most original and sui generis works one stumbles on in a lifetime” and compared it to Samuel Beckett’s “Not I” which Beckett hoped would “work on the nerves of the audience and not its intellect.” Is this the hope for your play?

I am hoping is that it will hit and strum the nerves of people in a way to get them to think about people in different ways and with more openness.

You were unhoused in Minneapolis for two years and would take pizza boxes out of the trash and write poems to give to other members of the unhoused community.

I was so scared by what was happening and the only thing I could think to do was some sort of art. Ever since I was five years old, art – writing, singing – was the only thing that kept me going. Being the optimist that I am, I assumed that everybody was as excited about these things as I was. I would write out things on a delivery bag and hand them to people I would meet on the street. I remember one poem that I wrote back then:

He fell but he did not hit the ground

He hovered a few inches above the snow

Forgetting gravity

Forgetting the way things are

He hovered after his fall

And breathed a new air

You have said, “To this day, I still feel very isolated and by necessity create my own world.”

Right now, I am working on a solo show about 10 years of my life when I was housebound, so I am doing a lot of thinking about why I was so isolated. But isolation also brought me a lot of joy and experimentation because I had to come up with my own forms and my own ways. I tried stuff and if it didn’t work, I tried something else. That’s been my life: I’m a kind of a tinkerer.

How concerned are you that a director or producer might alter your universe to make it more palatable to a neurotypical audience?

There has been a lot of rewriting of my work without my permission. It does concern me, but luckily, I am working with really great people at CATF. Peggy is one of the most supportive and open artistic directors that I’ve ever met. She has always wanted to do my play because it gave her a view she never had. You don’t ever get everything you want because of things like budget and all the things that go into a theater piece, but this production will get very close to everything the play needs.

If you had one piece of advice about life for a loved one, what would it be?

Gravy Land. A couple of years ago, I learned about the life expectancy of autistic adults with different co-conditions, and I realized that I had already hit my life expectancy years and years before the average. It was my birthday and I looked at my husband and said, “That’s a great premise, but instead of getting upset because I know those things are all so dependent on how you take care of yourself, it did make me think that I’m living in Gravy Land. Every day is gravy. Every day is a gift, and I have to decide, “Do I want to have a good time or a bad time?”

What is one question you wish an interviewer would ask you?

Today, the question would be, “What wisdom do young people give you?” Younger folks gave me words like nonbinary, various pronouns, and ways out of gender constructs that have always felt cage-like. Wisdom is multi-directional. I wouldn’t have words to help Chantal in Tornado Tastes Like Aluminum Sting liberate themself from the confusion of gender fixedness without the wisdom of young thinkers, activists, humans. Today, Chantal’s journey is even more important because of the increased violence aimed at trans and gender-nonconforming people. This is one of the definitions of family: providing context and standing up for each other.

What image immediately comes to mind when you hear the word, “family?”

Not so much an image, but the word, “friendship.” Family for me is a chosen family.

What image immediately comes to mind when you hear the word, “love?”

It feels like faux fur being rubbed across my skin and it sounds like music, but mostly it makes me think of my husband. When I was younger, I never thought anyone would want to be in a relationship with me. How lucky I am to have a husband as amazing and supportive as he is.