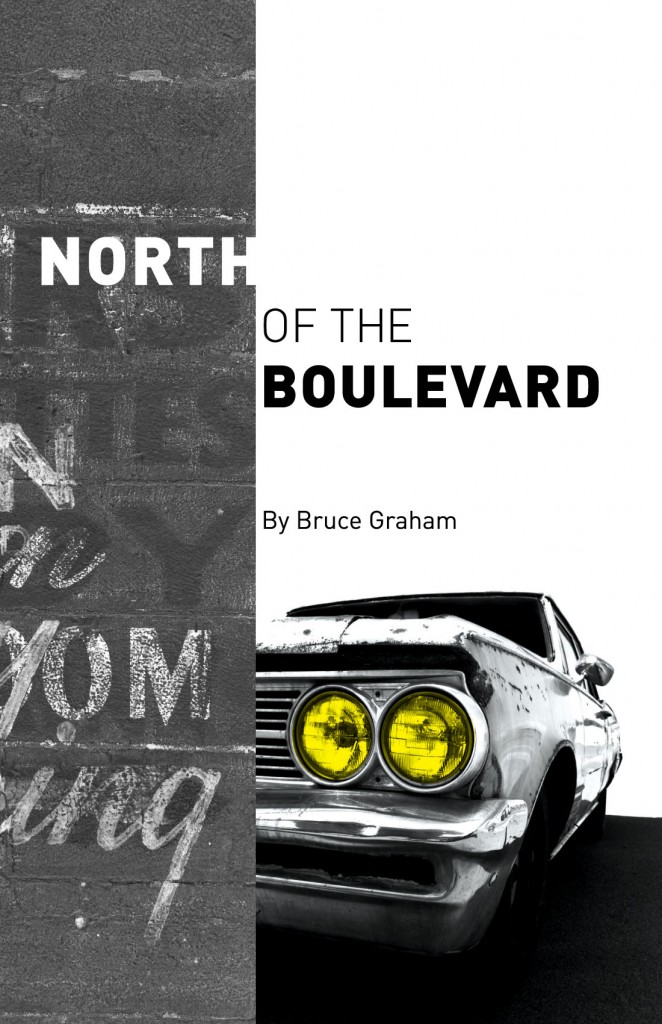

An Interview with Playwright Bruce Graham

Researched, interviewed, and edited

by Sharon J. Anderson, CATF Trustee/Professional Storyteller

CATF: You have said that you wrote, “North of the Boulevard” because “the middle class is getting totally screwed by this country.” Are you as mad as hell and not going to take it anymore?

CATF: You have said that you wrote, “North of the Boulevard” because “the middle class is getting totally screwed by this country.” Are you as mad as hell and not going to take it anymore?

GRAHAM: Oh, I’ll take it, but I wake up angry. This play represents the difference I can make as a writer. I’m not a political activist, so this is how I’m going to make my attempt at change. Also, your audience in theater is usually upper-middle-class-to-wealthy. Maybe I’m exposing something people never thought about before.

CATF: You also have said that you always want to give the audience something or somebody to “root” for. What are we rooting for in “North of the Boulevard”?

GRAHAM: Depends on your point of view. There’s a guy named Trip in the play and he faces a real moral dilemma and question. Some people don’t see moral dilemmas and questions. They just do it. Other people say, “Whoa, whoa, whoa . . . you’re making a kind of Faustian bargain here. Don’t do it.” I think people in this play are rooting that these guys can get better lives, with the exception of the old guy who is probably beyond redemption. These guys haven’t gotten the breaks in life that others have.

CATF: A description of this play asks this question about your characters, “Are they corrupt enough to escape the corruption that’s ruining their neighborhood?”

GRAHAM: Well, I have a favorite line of my own because I’m a typical American: I hate corruption until I get my piece. We all roll our eyes, but if someone slips you 30 grand do you take it or walk away? Quite frankly, I’m not sure what I’d do. I hope I would do the right thing, but we’re all on shifting sands.

CATF: How was being a stand-up comedian the best training you ever had as a writer?

GRAHAM: Comedy is immediate reaction. Your audience either laughs or they don’t, and if they don’t laugh, you’re back delivering pizzas. In the 1970s I worked in a couple of clubs with a partner, and I hated doing the same jokes twice. I had to write new material every week. If the sketch didn’t work during the first show, I’d be at the corner of Fourth Avenue leaning against a dumpster doing a rewrite for the second show. They don’t teach you that at Yale.

CATF: In all of your interviews as well as one-on-one, you drop one one-liner after another. Are these one-liners a way to protect yourself? Keep others at bay?

GRAHAM: Yes, they are. I’m a private person in a public business. Writers have to be hermits. Too many writers want to talk about writing. It’s the most boring topic in the world. I may talk about it with a couple of writer friends, but I really like my privacy. People like the one-liners because they believe they’ve heard something that sounds like insight so they walk away which is why I like one-liners.

CATF: You said that if you weren’t a writer, you’d be a serial killer.

GRAHAM: It’s nice work if you can get it. That would be an easier way to get out my aggressions.

STELLA & LOU by Bruce Graham at Northlight Theatre. Directed by BJ Jones. Pictured: Ed Flynn, Francis Guiman, Rhea Perlman. Photo by Michael Brosilow.

CATF: So that’s why your plays are called, “blistering” and “gritty”?

GRAHAM: Yes, but I’ve also written a play, “Stella and Lou,” now playing in Chicago with Rhea Perlman in it which is the sweetest, nicest PG-rated thing in the world. One of my most popular plays — perhaps my most popular — is called, “Moon Over the Brewery” and it’s about a little girl and her imaginary friend. I change from play to play. I get really bored writing the same thing.

CATF: Coleridge said that comedy was more useable and more relevant to the human condition than tragedy.

GRAHAM: Comedy comments constantly on the human condition. I just saw, “Laughter on the 23rd Floor” which had a dour ending to it and a lot of profanity for a Neil Simon play. People were shocked. Comedy will always comment on the human condition and not always in a nice way. Historically, any time dictators come to power, the first thing they want to do is to get rid of the clowns and the comics because ridicule has so much power. Nothing can make you look more ridiculous than being the butt of a joke.

CATF: Joni Mitchell’s album, “Court and Spark” includes this line: “Laughin’, cryin’ – it’s all the same release.”

GRAHAM: I love that album. And yes, it is the same release. Our shoulders hunch, we get short of breath – physically, they are one degree apart from each other.

CATF: You teach your students that a play must have a story and that there must have “universality”. What’s universal about “North of the Boulevard”?

GRAHAM: What’s universal about it with the exception of a very, very, very few people – we’ve all had to struggle at some time. It can be an emotional struggle or an economic struggle, but three of the characters in this play want a better life for their kids. I know my parents certainly did. I think that’s important to people even if you are in the upper income bracket. The characters are struggling and when they make you laugh, you suddenly care a little bit more about them.

CATF: Does that happen when a character makes us cry?

GRAHAM: Oh, no . . . my students are forbidden to write anything in which a character cries. It’s a cheap way to get emotion. If the character is on the verge of tears, that’s okay, but crying, no way. A character has to earn the right to cry.

Paul Sparks in the 1999 CATF production of COYOTE ON A FENCE by Bruce Graham; directed by Lou Jacob. Photo by Stan Barouh.

CATF: Do characters have to earn the right to make us laugh?

GRAHAM: No! Because laughing is fun! I personally don’t like displays of emotion, so I don’t put them in my plays too often unless it’s anger. My most heinous characters make you laugh before you find out that they’re evil. My play, “Coyote on a Fence” [CATF, 1999] is about death row and it’s somber for the first five minutes, but then the character is funny and the audience is laughing and then they find out what the prisoner did and they say, “Oh, my god.” So I’ve yanked their emotions back and forth. They don’t know how to think about this guy. The audience can’t get comfortable with the character because they don’t know how they feel about him.

CATF: The masks that symbolize theater – the comic mask and the tragic mask – both look like grimaces. The grimace of comedy resembles the grimace of tragedy. The masks seem to have the same distortion.

GRAHAM: I’ve always thought that. They freak me out. When I was a little kid, they scared me. But back to your point. If I slip on a banana peel, it’s comedy, but if you slip on a banana peel, it’s tragedy.

CATF: Coleridge said that comedy is a more pervasive human condition; that “the problems raised in the great tragedies are solved in the great comedies.”

GRAHAM: That’s interesting. You look at “Macbeth” and you see that Shakespeare stuck some comedy in there like the porter or the grave digger in “Hamlet”. My play, “Desperate Affection” features a hit man and the woman who falls for him. I approach his profession as a bad habit. That’s comedy. If I approached it as him really killing people, that’s tragedy.

CATF: You have said, “there’s a lot of anger brewing out there”.

GRAHAM: I’m not hip to “the meek shall inherit the earth.” I go to church once a year with my actor friends and this Easter, heard a great sermon that featured a story about how a priest in a country experiencing revolution was appealing people to forgive and move on. “I burned your house and killed your husband, but now I ask for forgiveness.” No way I would do that. I admire people who do that, but not me.

CATF: When your audience walks out of “North of the Boulevard”, what do you want us to be thinking?

GRAHAM: I want you to be thinking, “Why are these guys in this position?” I also want you to be thinking, “Okay, what happens the next day?” Or, “That’s not my life. How can I be more empathetic to people who have that life?”