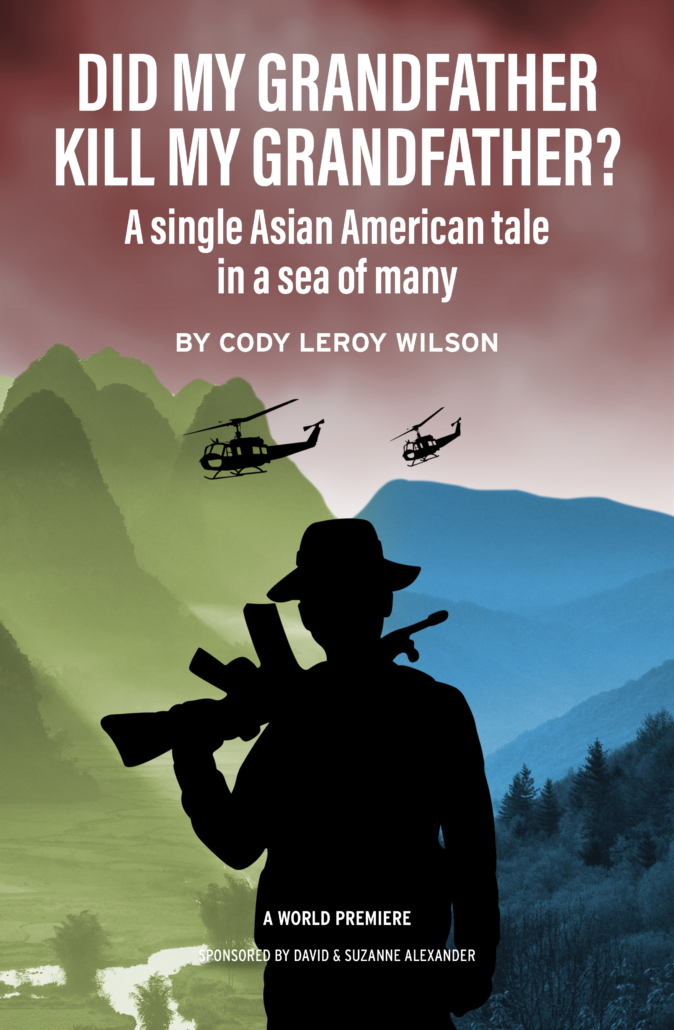

Meet Cody LeRoy Wilson

Cody LeRoy Wilson is a Vietnamese actor/playwright from West Virginia with a BFA in Acting from West Virginia University. Cody is honored to have his play, Did My Grandfather Kill My Grandfather?, have its world premiere with CATF. Previously, the play was workshopped during Pan Asian Repertory’s NuWorks Festival in 2023 in New York City. He also debuted another one-man show, Halfanese-Two Halves of a Whole Idiot, with Pan Asian during their 2024 NuWorks Festival. Off Broadway credits include: My Man Kono (world premiere) with Pan Asian Rep, Handbagged at 59E59 Theater during the Brits Off Broadway Festival. NYC credits include: Prisoners of Quai Dong with Prism Stage, Titus Andronicus and Midsummer with NYSX. Regional credits include: Book of Will, Handbagged (US premiere), and The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time with Roundhouse Theater, As You Like It at Folger Shakespeare Library, Measure for Measure at Hudson Valley Shakespeare. Film/TV include: Hello Tomorrow, Impractical Jokers, Russian Doll, 11 Blocks to Go, and Gravedigger “Pilot.” Cody dedicates this show to his family, those he is grateful enough to know and love, as well as the family he has never met from Vietnam. As a Vietnamese artist, it is Cody’s goal to uplift the stories and voices of Asian Americans everywhere.

Interview with the Playwright

Conducted and edited by Sharon J. Anderson

CATF: At the beginning of your play, you write: “The goal of the play is to take the images from my personal life experience and the daydreams of the story inside my head.” What were those daydreams?

CLW: As a kid, I felt like a zebra in a den of lions. I was aware that I was on the outside of the pack. In my daydreams, I wondered, “If I were to embrace all parts of me, what would that look like? What would an Asian in West Virginia look like?” So I started with Shakespeare and all these grand speeches with simile, imagery and metaphor, and thought, “That’s how I feel. I need to find more words to describe my ecosystem. If I could say everything I can feel, how big can I make it?”

Had your grandfather and grandmother told you about Vietnam?

No. It wasn’t censorship, it was a choice. My grandparents were very stern with their love, and did not want to talk about how we were different.

Your mother never said anything about your heritage?

No. When I asked my mother about what it was like in Vietnam, she said, “I don’t know.” That was literally the conversation. When I asked my grandmother, she said it was a very easy story: your mother was in an orphanage in Vietnam, and we adopted her and brought her home. Those simple facts. We didn’t talk about the war in our house, even with my grandfather’s PTSD.

In 2017, a Military.com article said this about Vietnam: “The war’s effects, it has been suggested, extend far beyond those who directly experienced it. The shadow of Vietnam falls on their children and grandchildren, who suffer from the psychological and emotional toll it takes.” In this play, are you trying to define the shadow?

Yes, I place myself in the shadow to uncover the shadow.

When I first learned about the Vietnam War in high school, I thought, “Oh, something’s wrong. Something here isn’t truthful.” All I heard was that America did everything right. We had all the means to do it and we did it well. While looking through books and seeing dead Vietnamese, I thought, “You all are championing this? How does no one else in this classroom feel empathy towards me right now?” It was terrifying. No one was being held accountable. I was in emotional turmoil and for everyone else, it was just an everyday history class. I never felt more displaced.

In your play, you write, “I knew that the Vietnam War was a chapter in American history that had a veil over its truth. If it were a painting, you would see water marks distorting the image, making it hazy and nebulous. If you stared at it long enough, your eyes would confuse you, and you wouldn’t know what lines were truly set and where they became blurred. Nowadays, we call them ‘fuzzy lines’ or alternative facts. It’s amazing how history repeats itself.” How is history repeating itself at the moment?

What I think is unforgivable is that we are in an era that allots for honest, vast communication, and the amount of abuse in that power is astounding. I’ve been listening to a new documentary series on the Vietnam War that features all of the hidden tapes between Kennedy and McNamara and LBJ. What you hear for the first time is the truth. You hear, “We don’t have the power. We can’t win this war,” but it gets to the point that they needed to give some good news to the American people, so they gave them body counts. “We’ll talk numbers. If we give them the body counts, we will show them that we are winning.” Now it’s a similar thing from election lies, to what Russia is doing to Ukraine, to how many immigrants we are shipping off. It’s all about numbers because unfortunately, the civilian population is easily manipulated. We have lost the ability to think critically because of, in my opinion, the cellphone. People choose what is comfortable and assimilate to those around them. We are damning ourselves by aligning for safety. My people against your people. How are we still doing that?

Your play includes many violent, powerful and brutal images from the way, including the immolation of a Buddhist monk.

I remember the first time I saw the image of that monk. I was still in high school, and I was amazed by how quickly everyone else could turn the page. Just because it happened decades ago doesn’t mean it wasn’t impactful. Some people grow up not understanding the gravity of history. The image of that monk stopped the world for half a second. In 1963, this monk set himself on fire, but more importantly, Kennedy was shot. That is the important part for America.

At the end of your play, you tell us that, “we each have a special, unique, sometimes heartbreaking take of how we came to be here. What I discovered about being Asian American is that it is ownership of your story. Not apologizing to the past you can’t change. Embracing what you know to be true: living life to the fullest by holding on to what’s most important to you. And above all else, knowing that you have the right to be happy regardless of the color of your skin.”

Empathy, if it is not taught, needs to be learned. The only way you learn about empathy is when you learn more about yourself. I learned to empathize with others because I realized my individual story was filled with empathy. If I feel this intensely about myself, I can only imagine what nine billion other people on the planet feel. As much as my play is about me, it feels like an “every man” play. The most amazing experience I ever had as an actor and an artist was after I previewed this play for the first time at the Pan Asian Repertory Theatre in New York City. Asian patrons came up to me to share their immigration stories from Korea, Japan, Thailand, The Philippines, etc. They had so much passion. I gave people permission to tell their story. It was awesome. Now I have a larger purpose that drives me more; makes me produce more work. I already have more plays dedicated to Vietnam that I am trying to curate. It became a mission statement: I am going to become a playwright for my people.

Do you gravitate toward one heritage over another?

Not really, because I love wearing flannels and hiking mountains, and I’d be lying if I said I didn’t like a good cup of moonshine. West Virginia is my heritage. I love that I can be a representation of these two vastly different peoples. My family in West Virginia was very rural and I love them unconditionally. I can’t tell you how much I learned from all of those people. Likewise, there’s this entire group of people that I’ve never met that I feel like I’ve gotten so much enrichment out of. I have this imaginative family where I feel like I am supported and loved and motivated by.

On your Instagram account, you share: “If you ever feel like your story isn’t enough to create art around, don’t count yourself out! Everyone has a tale, shout yours from the rooftops.”

I want to empower others. I never knew that was a goal.

What do you think of this line – a recurring theme — from Samuel Beckett’s novel, The Unnamable: “Words are all we have.”

That didn’t feel true for me for the first half of my life. Thought was all I had. Words are spoken, and I left so many things unspoken. I had crippling social anxiety. I didn’t want to talk to people. Then I became an actor. When I started to speak in college – and it really was through the power of Shakespeare – I finally got words that mattered. I realized that my voice has strength. And as I write and as I perform – even if it’s in the smallest role, sometimes literally five words – those are the words I have. Neil deGrasse Tyson said, “People will say, ‘like’ and ‘um’ because they are not thinking about what they want to say.” If words are all you have, you should probably think about what you want to say.

A Letter from Cody LeRoy Wilson for CATF’s Weekend of Giving

My name is Cody LeRoy Wilson, I’m the first West Virginian playwright to ever be produced here at The Contemporary American Theater Festival; it is my greatest honor to be able to share my family’s complicated and beautiful story with the audiences here at CATF. As the first-generation son of a Vietnamese immigrant, born and raised in rural West Virginia, my life has been filled with an array of complexity, and my play Did My Grandfather Kill My Grandfather? Is my lifelong attempt to unpack the weight that my upbringing gave me. American Theater is at a tipping point, where the want to tell human stories is being overruled by the circumstances of business and the industry. CATF is producing bold, new, innovative, compelling, and personal theater. I am truly blessed to be sharing the season with other autobiographical stories (Kevin Kling’s Unraveled and Lisa Loomer’s Side Effects May Include) and have hit a new turning point in my career because of the support and mission of CATF. I am reliving the moment in my life where I knew I wanted to perform; in high school I watched my first play, it was about students taking a test to see if they could get into heaven. I was compelled to investigate the craft of performance and joined the theater after seeing the show! The feeling I had of discovering a path of expression and a calling to follow the rest of my life was born. And here in Shepherdstown WV, that same feeling has been reborn again. I now see my career turning in a new trajectory, I want to be a Storyteller. Not just an actor, but a human willing to share their tales to others and in doing so heal the wounds audiences carry inside their hearts.

I’ve been acting for over a decade and nowhere else in the country I’ve worked has the same nurturing and supportive team that CATF brings. Here, they are brave enough to tell fearless stories that other theaters would be too scared to take on in their season. With the support CATF provided, I was permitted to explore my voice as a writer as well as a performer; they allotted writing workshops in NYC and Savannah, GA prior to arrival which offered time to perfect the play. There is a force here that can’t be matched. Bringing high caliber theater to rural audiences is breathtaking, but to fund the development of new plays is truly special; CATF is a haven for new American Theater. Even better, CATF is the starting place for so many great shows to travel the country and the world. I grew up on a farm with very little, thinking my family’s story would wash away with time, but now I get to live my childhood dreams to the fullest and tell my story. As a person of color, I’ve never felt more seen, heard, respected, cared for, and lucky to be with such a loving company and community. I hope you can find it in your heart to help continue the work here at CATF; miracles are happening this season and I know they will continue blessing the great state of West Virginia.

I’ve always claimed West Virginia is my true home and I cannot express the gratitude in which I feel to come home and connect with so many people. Those “Country Roads” have indeed brought me home to Wild and Wonderful West Virginia! I hope you can continue to support CATF in the future, the work being done here is unmatchable in effort, character, development, and love. And you can help bring the next great piece of American Theater to life here in Shepherdstown, WV.

Be Well,

Cody LeRoy Wilson