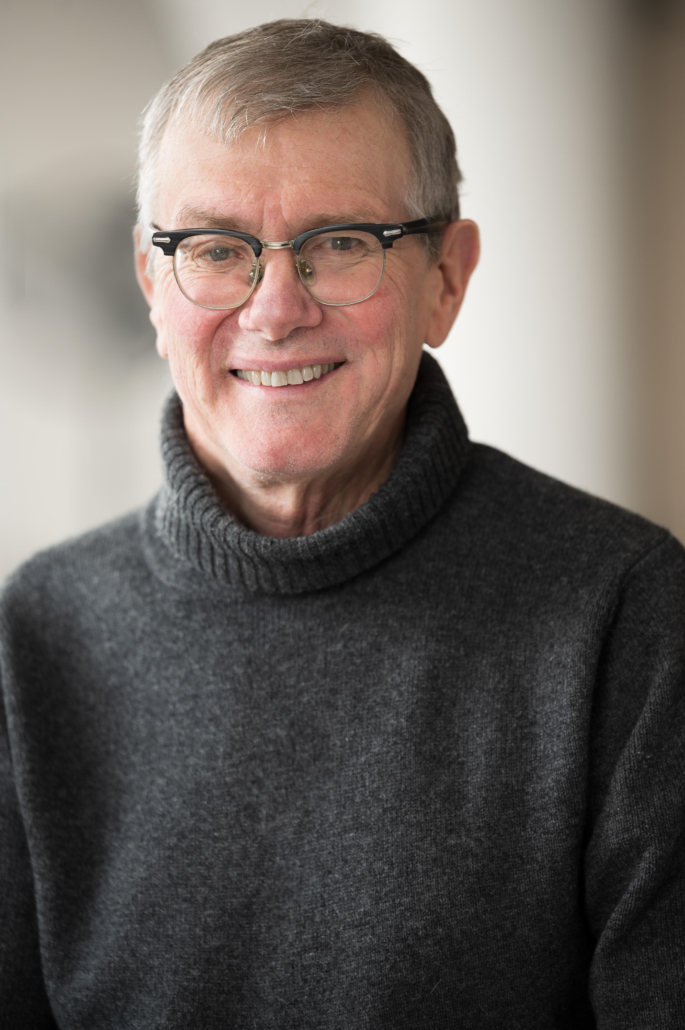

Meet Kevin Kling

Kevin Kling is very excited to premiere Unraveled at CATF, adding to over 40 years of collaborations with his friend Steven Dietz and, more recently, the brilliant Rob Witmer. In 2023, they premiered Best Summer Ever at the Merrimack Repertory Theatre. Kevin’s plays have been produced by the Guthrie Theatre, Seattle Rep, Cincinnati Playhouse, Sydney and Perth Arts Festivals, Spoleto USA, Actors Theater of Louisville, the Goodman, Children’s Theatre Company, Denver Center Theater Company, off-Broadway at Westside Arts and Second Stage Theater, and many others.

Commissions include the Minnesota Orchestra, the Zeitgeist Ensemble, and the Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra.

Kevin has been awarded an NEA Grant, Whiting Award, a McKnight Fellowship, a Bush Fellowship, and two Upper Midwest Regional Emmy Awards.

As a storyteller, Kevin has toured the US, Europe, Australia, and Thailand. He is a frequent performer at the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough, TN. Kevin has written five books, produced seven CDs, and has performed often on PBS and NPR’s All Things Considered. He is the Minneapolis Storyteller Laureate.

Interview with the Playwright

Conducted and edited by Sharon J. Anderson

CATF: In your play you observe, “I do know that sometimes life gives you answers before the questions.”

KK: A lot of that has to do with the world of disability. One of the answers is that underneath, we are all more alike. A way that a lot of people treat disability is through fear – fear of it happening to themselves. Once you get past that fear, I generally find that there is compassion. That’s an answer I carried even as a kid. When other kids were bullying or treating me as “another” when I was a kid, I let it shed off my back. In doing that, I created a more appealing world than the one they were living in. When you present a better world, people jump aboard. That’s not something that comes from the outside, but from something that we all carry.

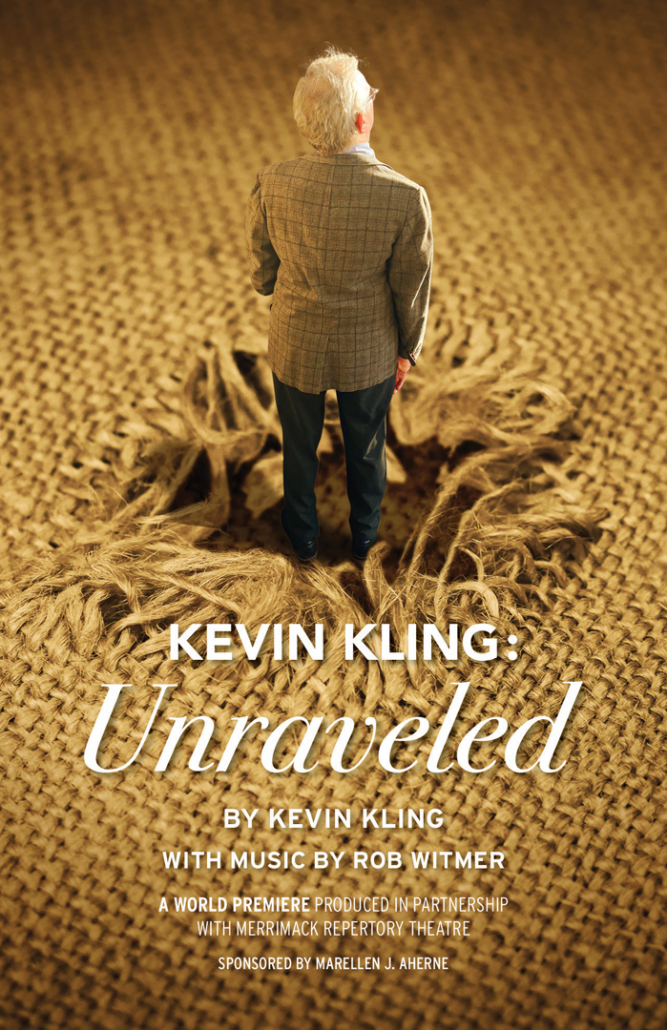

You call yourself “a weaver of stories, constantly looking for patterns, connections, and unexpected intersections that connect us to one another and to the world” that you unravel. What have you had to unravel in your own life?

It’s pretty typical stuff – family stuff especially, including the family stuff that was passed down: biases and different “isms” that we carry with us, even DNA strands. How do we unravel DNA strands that subject us to different kinds of behavior so we recognize them when they happen and are not predisposed to those behaviors? There’s a lot of unraveling that happens way before being born. That’s why I am so drawn to mythology and the pantheon of stories. Freud said, “Wherever I’ve been, a poet has been there first.” Our poets have broken so much ground before any science. NASA started to hire storytellers because, according to a NASA official, “We keep shooting scientists into space and poets come back.”

In your play, you share that Thomas Merton could not worship a god he could understand: “If you’re a poet and a Christian, be a poet first because if you aren’t any good no one will want to be a Christian.”

I am pretty sure that I am paraphrasing, but I found that really powerful. We don’t expect monks to say things like that Martin Luther said, “I wish I could pray like the dog looks at meat.” If we could be like that, we would be fine.

Do you read poetry? Do you have a favorite poet?

Yes, I read it, and my favorite poet is Michael Brindley who is in a theater company here in Minnesota called Interact. Michael has Down’s Syndrome and writes poems that have questions within them that are beyond my grasp. One of the beauties of being an artist is bringing people into a perspective that they don’t expect, and opening the world in a way they don’t expect.

Wisdom isn’t discovered, it’s recognized. We compile all this knowledge through our lives, but wisdom is when there is a recognition of a truth that runs both through us and through the source. Truth needs to catch us by surprise before our walls can go up.

“Paradox is this ability to hold two opposing thoughts at the same time . . . we need paradox to figure things out,” you share in your play. What is an example of paradox in your life?

It may just be me, but when I encounter something in my brain, I bring up its opposite and usually the truth is in between the two. It kind of happens every time I talk with my wife. We immediately bring up the other side. Part of our relationship is that we love living in this paradox. She told me once, “I don’t know if we would be together if I could understand you.” A lot of people need to be understood, to find their “soulmate,” but my soulmate is somebody on the other side; somebody that I don’t understand.

“Stories weren’t meant to explain the world,” you write in your play, “they were meant to place us within the world, as part of the mystery because even better than to explain it is to belong. We are part of the mystery.” What mystery?

Whatever the great mystery is. One of the biggest surprises of my life is the friendship I have developed with an explorer, Will Steger, who has done unprecedented things like crossing Antarctica the long way. One of the biggest surprises of his life is providence. He doesn’t necessarily agree that something is taking care of us, but the more you discover that your life is at risk, the more you discover that something greater is going on that we are all a part of. Sometimes people think of providence as that which can save us. But he thinks of it as something that envelops and holds us. That is one of the truths that I can feel more than I can describe.

What distinguishes a great storyteller from a good one?

The moment in which the story is being told. The story lives in its moment. The storyteller is beholden to this moment. The best storytellers are either in their eighties or their nineties. It is undeniable that it takes many years to become a great storyteller. One of the greatest was Kathryn Windham who lived until she was 94. Nobody could hold a candle to her. She lived in Selma, Alabama across from her best friend, Harper Lee. She was the first woman journalist for the Alabama Journal and covered the march across The Edmund Pettus Bridge.

In your play, you admonish your audience to “Listen to the point of invisibility. Listen to the point of empathy.” In the constant chatter of the modern world, where no one seems to have the time or even the desire to listen to anyone else, how can we listen better?

Find stillness, that place where you can be the sounding board, the reverberation of the sound. The world is in constant motion. There’s a great saying in birdwatching, “We enter the field with two energies – disturbance and awareness. The disturbance in time gives way to the awareness.” A birdwatcher went to the same field for four years and finally heard a bird he had been looking for. He said, “That bird was there the whole time, but it took four years for me to get to the point where I could hear it.”

Maya Angelou said that, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.”

Wow, that’s a good one. It’s like harboring a fugitive.

The director of your play is Steven Dietz . . .

Yes, and we are best friends. I’ve known him for more than 40 years. There are so many layers to him in terms of playwriting and production. When you get Dietz, you get a dramaturg, an incredible director, an incredible playwright, and an empathetic listener. He will hear things that he will bring back to you. He brings stability to a production that makes for a wonderful sounding board. He’s absolutely brilliant.

What’s your secret for staying so ebullient and positive?

I don’t know if I actually am. Some of the most pessimistic people I know are really happy on the inside. I wonder sometimes if I’m happy on the outside to convince my insides. I might be a pessimist in real life; it’s just trying to convince myself otherwise. Again – another paradox.

What do you think of this line – a recurring theme — from Samuel Beckett’s novel, The Unnamable, “Words are all we have.”

That’s not true for me. A friend of who is a third-year law student now has aphasia* so it is very difficult for thoughts to become words. She once said, “I used to believe, ‘I think therefore I am,” but after my aphasia, now I know “I am, therefore I think.” That opened a door for her where she realized that she comes from a place that proceeds thought. Words are connected with thought. We do frame our world with words, and so much of how we view the world is through words. Words definitely color our thoughts, but I do think we come from a deeper place.

*Aphasia is a language disorder that results from brain damage, typically due to stroke, but also from head injury, brain tumor, or infection. It impairs a person’s ability to communicate, affecting their ability to speak, understand, read, and write. Aphasia is not a disease itself, but a symptom of brain damage in areas responsible for language.

A Letter from Kevin Kling for CATF’s Weekend of Giving

Dear Theater Patron,

Over the years I have participated in many new play festivals, including the O’Neill, Sundance, Actors Theater of Louisville, the Playwrights Center, and I now count the Contemporary American Theater Festival among the greats.

The support and artistry of the staff, interns and apprentices, the artistic designers and stage managers are among the best in the country. The play I presented brought its own set of challenges, and I honestly can’t imagine another artistic team meeting those challenges and surpassing my dreams for this production.

Other playwrights I’ve spoken with here feel as I do. And to be part of a community that supports work that so boldly and beautifully addresses our world’s troubles and triumphs has been a complete honor.

I am also beyond grateful for the audiences. They not only brought open hearts, but I am hard pressed to recall a more theater-savvy group of people. And because of that, I was able to take my play much further than I originally intended and grew as an artist.

In these unprecedented times arts organizations need our support. As one who has benefited as an artist and audience member I can safely say that any donation to CATF is money well spent. Their work is crucial in understanding ourselves and other communities, to recognizing wisdom from folly, to feel we belong, and to live better lives.

The future of American theater depends on you now more than ever.

Kevin Kling