Researched, interviewed and edited by Sharon J. Anderson, CATF Trustee/Professional Story Listener and Creative Director www.sharonjanderson.com

Researched, interviewed and edited by Sharon J. Anderson, CATF Trustee/Professional Story Listener and Creative Director www.sharonjanderson.com

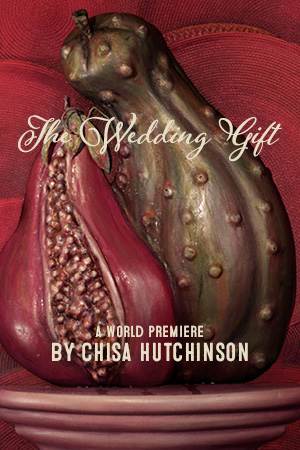

CATF: Audiences are going to be challenged by “The Wedding Gift” for several reasons. One, it features full-frontal nudity. Two, the actors speak in a language you created, often without the benefit of a translator for about 30-40% of the play. That being said, the audience is facing an even deeper, more profound challenge. How would you describe that challenge?

CHISA: The intention behind the language is to disorient the audience so it experiences a world that parallels the main male character – Doug. Doug is human, but he’s treated like an animal, a pet, a male concubine, eunuch . . . he’s basically a slave. The challenge of the play is to be able to identify with the slave; to forge an empathetic connection with Doug.

CATF: You say this play is about what it means to be “the other.” It just not blacks among whites or whites among blacks, but also gays among straights, transgendered among males and females . . . even sick people around healthy people. We all have to learn to speak a language that others don’t always understand. You would know that, of course, because of your multiple sclerosis.

CHISA: Absolutely, and I hope that audiences will be able to fill in the blanks for themselves, i.e., “This is the thing that makes me ‘the other.’”

CATF: Are you concerned that some in the audience won’t get the heart of this message – empathy for the slave or “the other” because of the nudity? Won’t some walk out of the theater saying, “Doug was naked,” instead of “I care for Doug?”

CHISA: Doug is not naked during the entire play. It may become a little distracting, but in one scene it is totally necessary for Doug to be naked. I never use nudity in a gratuitous way. Like with “Dead and Breathing” two years ago at CATF, it’s all about the vulnerability of that character in that moment, that sense of exposure, that helplessness. Having someone naked standing in front of you is totally different from seeing someone totally naked on screen. You are forced to think about the choice the writer made. You have to grapple with it emotionally.

CATF: Two years ago you said that you “wrote plays to make myself and others like me more visible.”

CHISA: When I wrote “The Wedding Gift,” I had in mind all these movies and plays that depict slavery in a hyper-literal way, i.e., “This is EXACTLY what it was like! Here are the scars and here is the blood . . . look at it!” That’s one way to come at it. But, ironically, I feel like it’s desensitizing and distancing. It makes it very safe for folks to respond, “Oh look how horribly they were treated so, so long ago. Isn’t it great that we don’t do that anymore?”

Black people are still chained today. Look at all the police brutality. I recently wrote a short play that was intended to be a reading of the names of women fatally brutalized by police, or women who had mysteriously died in police custody. After extensive research, the list turned out to be all women of color. I thought, “Wow, that’s telling. You cannot be in your skin without being targeted. Your skin makes you a bulls-eye; a magnet for that kind of violence.” It’s really hard to be confronted with the fact that my own skin is a prison.

CATF: At one point in the play, Doug says, “You consider me an animal, something less than you, but I’m supposed to trust you with my life?”

CHISA: I’ve definitely been in that position, maybe not with the police, but definitely with doctors. Recently, I had a horrible reaction to some MS medication. I had palpitations and trouble breathing and was drifting in and out of consciousness because I couldn’t get oxygen. My face went numb, my hands went numb . . . I actually had to be carried into the ER. The nurse in the emergency room said out loud – she probably thought I couldn’t hear her – “Ehhck . . . drama queen junkies.” I wanted to say, “Hey, I can hear you.” This person was supposed to be saving my life, but was making a quick judgment about whether or not my life was worth saving. You trust your doctors, you trust police officers, you trust firemen, you trust teachers – these positions come with inherent trustworthiness. When you see someone you’re supposed to trust thinking, “that doesn’t apply to me,” it’s sobering, it’s discouraging, to put it kindly. It’s infuriating.

That’s where the character Doug is in my play. He’s confronted with this reality, “I’m really helpless here. I have no power here.”

CATF: So “The Wedding Gift” is also about power and the fact that none of us can really control anything?

CHISA: For Doug and for a lot of us, especially brown folks, it would be enough just to be in control of our own bodies; to not have our bodies policed or tampered with. It would just be enough to be in control of our own personal situations, to have some agency, if nothing else. I don’t need power. I just need the freedom to be me.

CATF: Let’s talk about the vocabulary of this play. Does your made-up language have a name like, English, Spanish, French?

CHISA: No, it doesn’t.

CATF: Did you begin with phonetics – what the words sounded like?

CHISA: I did. I had every intention of making the language just gibberish, but I’m a word nerd, man, and really geeked out. Then I thought if I’m not going to provide subtitles or translations, there has got to be some recognizable words. You have to know the word, shimseh. You have to know that that’s Doug; that’s his position in the world, what they consider him, the pet. There are other words that people will recognize.

CATF: Let’s look at the personal pronouns: I, you, we, they, she, he, it. In your made-up language they translate to Esh, Tesh, Kesh, Desh, Sesh, Besh, Vesh. How did you assign the consonant at the beginning for each one of those?

CHISA: Desh just sounds like “they” to me. Sesh is very feminine so I assigned it to “she.” The “b” in Besh sounded very aggressive so I assigned it to “he.” Then I kind of ran out of consonants that made sense.

People who are multi-lingual have read the play and have asked me if I studied some language that I absolutely never studied. Or they tell me that the language is constructed just like German. Aren’t languages all pretty much constructed the same way? They all have those pronouns, for example.

CATF: Toni Morrison has said, “We die. That may be the meaning of our lives. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.”

CHISA: It’s certainly true for writers. I’m writing play number 14 or 15, so I definitely feel like I’m measuring my life out in language.

CATF: You have said that you “see theater not only as a profession, but a priority, period.” Why a priority?

CHISA: Theater is a great way to teach a lesson or to foster empathetic connections that make it easier for all of us to survive and be happy. The quickest way to do that is live narrative. Theater can do things that engineering can’t do, that medicine can’t do . . .

CATF: . . . that poetry can’t do?

CHISA: Yes, in a way. Not to bash the genre, but poetry is definitely for lovers of words . . .

CATF: . . . and theater is for lovers of . . .

CHISA: Story. Film and television are pretty close seconds, but again, there’s nothing like having a live shaman in front of you presenting some truth about life and how to live it or how not to live it. It’s more visceral. I’m constantly surprised by theater and it’s capacity to speak to specific, individual situations. That’s why I will never get tired of playwriting.

CATF: I recently watched a short video of you talking about fragility. In it, you say, “Me and fragility – we cool. It gives us the opportunity to be our most creative, innovative, resourceful selves. As long as we acknowledge and embrace that we are fragile, we give ourselves the power to do amazing things.”

CHISA: It’s said that “necessity is the mother of all invention,” but necessity springs out of a place of fragility and vulnerability. We don’t like feeling like we can’t do things. We will do whatever it takes to not feel fragile, to not feel weak. We will do anything to give us an advantage. If people didn’t have diseases like MS, they wouldn’t be compelled to exercise whatever muscle it is that helps us to create; that drives doctors and researchers to come up with a solution to MS.

CATF: Jung said, “There’s no coming to life without pain.”

CHISA: YES! THAT! EXACTLY THAT! If you just felt perfectly fine all the time, where’s your motivation to do anything? Where’s your passion? Where’s that thing you live for? There wouldn’t be anything if we weren’t dissatisfied with ourselves about something; if we weren’t unsettled by our own fragility.

CATF: What distinguishes CATF from other theater groups and festivals?

CHISA: My experience with CATF with my play, “Dead and Breathing” two years ago is my absolute favorite production experience so far. It’s the fearlessness, the devotion . . . more than just the financial resources. The people who work at CATF are just so determined to make sure that the production is true to the playwright’s vision. And they work tirelessly. The results are always beautiful.

CATF: Is there a question you wish an interviewer would ask you?

CHISA: Not really. I like going along for the ride. The interviewer is driving and you just respond.

CATF: Is there a question you would refuse to answer?

CHISA: I haven’t encountered one yet. I’m a pretty open book.

CATF: Maria Irene Fornes said, “We can only do what is possible for us to do. But still it is good to know what the impossible is.” What’s the impossible for you?

CHISA: Considering where this country is, I would say trying to convince someone who is voting for Trump to not vote for him. Some people’s minds will never change no matter how many plays you write. I realize this when I read comments related to Trump or Black Lives Matter. You fight the good fight. You try to be rational and present a different perspective, but some people’s minds won’t be changed, period. That’s sad, but that won’t stop me from trying.

Researched, interviewed and edited by Sharon J. Anderson, CATF Trustee/Professional Story Listener and Creative Director

Researched, interviewed and edited by Sharon J. Anderson, CATF Trustee/Professional Story Listener and Creative Director